Coordination Without Constraint

Why the SEC and CFTC’s shared vision risks serving as regulatory cover for excess

The Davos Fracture revealed the competing visions for the future of American finance.

Speculation By Design exposed the regulatory gaps around crypto and prediction markets.

We ended that piece with a provocative question:

Are we there yet?

Are we driving toward a financial future that democratizes and protects?

We’re not. If anything, we’re drifting in the opposite direction.

Today’s piece explains why, and with it, we close this unofficial three-part series of this week.

A New Era of Coordination

The SEC has had Project Crypto for several months. Now that Selig is fully in charge, the CFTC has unveiled its own initiative: Future-Proof.

And last week, the new heads of both agencies stood side-by-side to tell America how they intend to cooperate toward a shared vision.

Spoken on a high level, in theory, that sounds all well and good.

In practice, the SEC and CFTC’s grand coordination effort mistakes permission for prudence. It functions as regulatory cover–an implicit green light for American financial nihilism at a time when the public needs more protection than ever. The underlying theory appears to be based upon: America wants to trade everything, so let’s give them everything, prudence be damned.

Beneath the forward-looking language lurks all the hallmarks of a reckless expansion, and ultimately a major crisis. We are convinced the road ahead leads to disaster.

To understand why, we need to look through a historical lens. A former SEC Commissioner’s reflections from 1982 offer a surprisingly sharp parallel to present day regulatory affairs.

Growing Pains

Historically, the SEC and CFTC have not been close collaborators.

The SEC is the older sibling –born from the wreckage of 1929 and formalized through the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.

The CFTC arrived four decades later in 1974, created by the enactment of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission Act of 1974. It wasn’t a response to a single crisis per se, but to a rather messy patchwork of state regulations, decentralized futures trading and confusion over what constituted a commodity. Congress centralized oversight and gave the new agency broad authority. After the 2008 recession, it was granted even more power.

The U.S. ended up with a globally-unusual, two-tiered structure. Canada’s Ontario Securities Commission (OSC), for example, oversees securities and derivatives under one roof. The path the U.S. chose has sparked turf wars from the very start.

To understand how these early tensions were viewed in real time, it’s worth revisiting the contemporaneous reflections (PDF) of former SEC Commissioner Bevis Longstreth, writing in 1982.

The regulatory siblings were arguing. Counterintuitively, that may have been healthy.

Inter-agency Competition

Longstreth took the long view with startling foresight:

Looking, then, to the future, the most significant aspect of the accord is that it opens the way for competition among financial instruments across jurisdictional lines.

He could have said this in 2022 and would have been just as apropos.

He continued:

With many products in the pipeline, one can safely assume that… the growth in financial futures and options will continue apace.

A safe assumption, indeed.

Ladies and gentleman: We give you crypto futures and binary options on sports events.

He noted that the profile of the market was shifting:

Ten years ago, traders in the futures markets consisted almost entirely of commercial groups engaged in business-related hedging and a small number of professional speculators. Today, increasing numbers of non-professional hedgers and speculators are being attracted…

At least there were some hedgers back then. Today’s event contract markets are dominated by pure speculation.

Longstreth also predicted competition between products overseen by the two agencies. That prediction came true–though not in the way he imagined. The CFTC barely “approves” anything anymore; the CFMA of 2000 and its self-certification process hollowed out that function.

But the deeper question remains: Is inter-agency competition good or bad?

Longstreth offered two scenarios.

Scenario 1: Productive Tension

With lines of communication open, the agencies may benefit… One would hope that… the agencies would tend to adjust their regulatory schemes to adopt the most effective and least costly means of protecting the public and otherwise serving the public interest.

This is the optimistic view: Competition as a laboratory for better regulation.

Scenario 2: A Race to the Bottom

Longstreth quoted former Fed Chair Arthur Burns:

"[T]he present system is conducive to subtle competition among regulatory authorities… to relax constraints… to delay corrective measures…”

Longstreth also quoted former Senator William Proxmire, who introduced legislation to…

…remov[e] the incentive…“to regulate all institutions at the lowest common denominator level…”

Lowest common denominator.

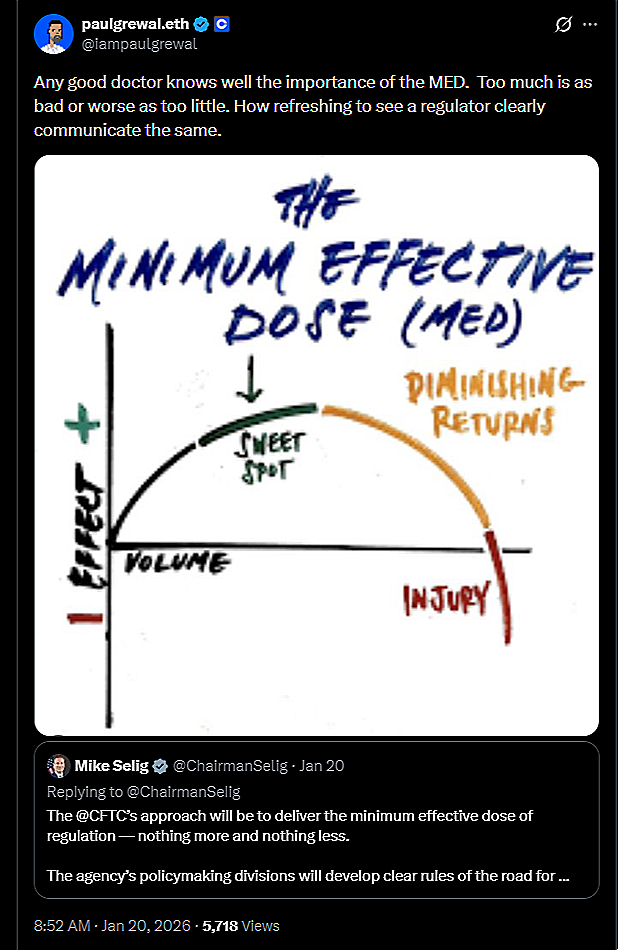

Sounds eerily similar to the minimum effective dose of regulation approach the CFTC is adopting.

You know, the framework Coinbase praises:

Predicting the Future

Longstreth ultimately chose optimism:

Regulatory differences will be eroded… but not at the expense of the investing public. (emphasis added)

His reasoning:

First, significant competitive advantages derived from regulatory differences cannot last. They will prove intolerable. Second, my experience with these agencies suggests that each, motivated by the public interest and a congruent instinct for survival, will stand by its public trust, despite the temptation to resolve the differences through a “competition in laxity.” (emphasis added)

Motivated by public interest? Doubtful.

Instinct for survival? Perhaps, but survival of what, exactly? The agencies or individuals preparing for the revolving-door landing pads?

As for the investing public not being harmed? The harm is already widespread. And the dangerous echo chamber (podcast) calling everything an “investment” only accelerates it.

Longstreth’s optimism feels increasingly misplaced.

The Video That Won’t Age Well

It’s true that the last administration ignored some rules and laws on the books.

The Biden-Era SEC took a tough stance on crypto–but lost the war because it misunderstood what investing means or how that definition flows through the statutes.

The Biden-Era CFTC took a tough stance on prediction markets as well– but lost because it misunderstood what gaming means.

The goodwill may have been there. The linguistic clarity was not. The American public, the real stakeholder, paid the price and will likely continue to do so through this administration, and potentially the next.

Under the banner of modernization, the current administration is doing worse. They’re not even pretending. Crypto, fine. Prediction markets? Fine. Everything is just fine and dandy.

The laws were misunderstood before. They’re being ignored now.

Ex-commissioner Pham’s advice:

[S]peed is of the essence... [Y]ou craft good, thoughtful rules, and then those will stand up in court when they get challenged.

Translation: The industry is moving fast and breaking things, so as regulators, we need to move fast too. What they’re doing is questionable at best, so expect legal challenges. Courts no longer defer to agencies, so the best insurance policy is Congress.

Make no mistake: This is not about “future-proofing” America.

It’s about “future-proofing” the industry–and the regulators who are supposed to protect the public.

Closing Thoughts

The SEC should function as a label regulator, making clear that crypto is not an investment product.

The CFTC should return to its roots, drawing a bright line between gambling and futures.

Instead, the SEC ceded ground to the CFTC on crypto–on a pair of false premises:

that crypto is an investment; and

that if something is a commodity, it cannot also be a security.

Past enforcement actions were mischaracterized as “regulation by enforcement,” and the Biden-era posture was dismissed as political theater. Both narratives were wrong.

Meanwhile, the CFTC–after sitting on the sidelines not for a year but for seven–has reemerged not as a cautious steward, but as an active proponent of sports gambling. The proposed 2024 rulemaking on event contacts and the staff advisory are now officially gone:

Worse, the guardrails for Americans are nowhere to be found. What could go wrong?

The result is exactly what Longstreth warned about: Competition in laxity.

And this time, it’s not subtle.

It’s open, coordinated and justified under the banner of modernization.

The cost will not be borne by the agencies.

It will not be borne by the platforms.

It will be borne by the “investing” public–the very group the SEC and CFTC were created and tasked by Congress to protect.

On this present course, it seems history is doomed to repeat itself.