Is Polymarket Really Worth $8 Billion?

Valuations get wild when finance and gambling share the same playbook

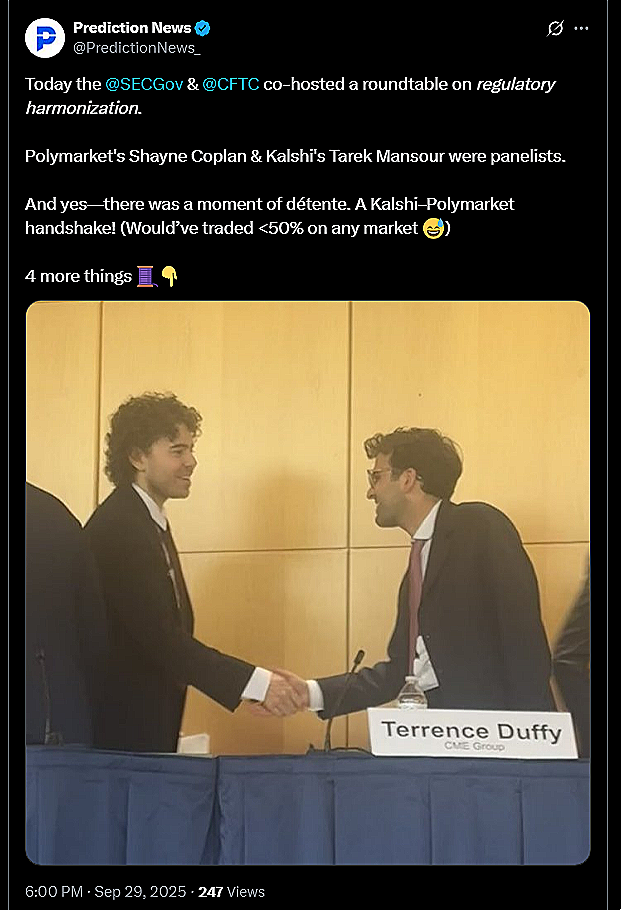

Two guys were on a panel last week…

If we told you it was prediction markets-related and asked you to guess who we’re talking about, you’d probably say Shayne Coplan, CEO of Polymarket, and Tarek Mansour, CEO of Kalshi. These two companies are locked in a fierce battle to capture the next generation of traders… uhm, gamblers.

Coplan and Mansour don’t like each other. Okay, maybe, it’s not Kobe and Shaq, there was at least a handshake and eye contact, after all.

But it’s not exactly buddy-buddy either. The best way to describe their current relationship, perhaps, is that they don’t like each other–but they may need each other.

Back to our guessing game: Coplan and Mansour sitting together on a panel is newsworthy, so it would’ve been a good guess–just not the best one. What were the two doing on an SEC/CFTC harmonization panel anyway?

Turns out the real headline was Coplan and Jeff Sprecher, Founder, Chair and CEO of Intercontinental Exchange, Inc. (NYSE: ICE), sitting in a panel together. And not just together–right next to each other.

Was that a coincidence? Knowing what we know now, perhaps not.

Here’s the ICE press release.

Andrew Kim nailed it with his comment–trying to get prediction markets into the mainstream, or shall we say, onto Main Street, seems to be the real objective here.

So, the deal values Polymarket at $8 billion pre-money. Just a few months ago, they raised $200 million at a $1 billion valuation. Did we mention prediction markets are moving fast?

We’d Love To Be A Fly on the Due Diligence Wall

A deal of this caliber generally takes months. Okay, prediction markets move fast, so maybe deal timelines get compressed when the company being invested in is itself a prediction market. But still, months, right? We doubt it was weeks and certainly not days.

There’s financial due diligence, there’s tax due diligence, and there’s legal due diligence. These lanes matter in every deal–small or large, public or private. This is a massive deal: A public company taking a meaningful stake in a private one; those lanes become even more consequential.

Put all of that together, and a reasonable inference is that somebody out there looked at Polymarket’s legal positions and got comfortable. Perhaps it was a red flag, but not a dealbreaker. Perhaps it was assessed as medium risk with a bit of a price concession. Or maybe–just maybe–it was a non-issue. This is prediction markets and the lines are blurring anyway. It’s not out of the question that it wasn’t even flagged.

We don’t know, and unless the due diligence deck surfaces one day in a court proceeding or elsewhere, we likely never will. What we do know is that the prediction market theater is going strong.

One could argue that Kalshi and Polymarket have similar risk profiles. To be sure, their paths to existence diverged: Kalshi took the CFTC head-on in court, while Polymarket settled with the CFTC first–and Coplan survived an FBI raid later. But today, both companies find themselves in roughly the same spot: Heavy reliance on sports, then elections, then everything else.

To be clear, we don’t think Mansour’s hand is as strong as he thinks it is. His company emerged on this side of the law only because the CFTC had a sudden change of heart, and then dropped the appeal right when it looked like the Court of Appeals was leaning toward the resurrection of the economic purpose test (if it was ever dead), and away from both parties. It’s difficult to say the issue was fully litigated. This was… half a case, at best. We believe Kalshi’s story is far from over.

Coplan’s stance is similarly problematic but he went further, deciding to play the provocateur. We’re having an SEC/CFTC harmonization meeting, and a prediction market entrepreneur elicits a middle finger from the head of a revered financial institution? This is not the country we used to know.

One wonders whether all of that is just a calculated wager on Coplan’s part. When he agitated Duffy and got flipped off, he immediately turned that into an advertising opportunity:

Or maybe it was cockiness on display. Hard to resist the temptation–if an $8 billion dollar deal was signed off on (or really close), just waiting to be announced to the world in a few days.

Whether that confidence is warranted is a different question altogether. Our take is simple: The boundaries between finance and gambling are blurring so quickly, the legal risks are likely not being priced correctly. Multiple scenarios could play out, but at least three could leave Polymarket with a fraction of the markets it operates today–turning the business into a shadow of its former self. (This post is not legal advice, please do your own due diligence and consult your own attorney)

When Coplan took the mic at the panel around the 30-min mark, one of the first things he said was:

You may be seeing the odds.

We have seen them, Shayne. And they don’t look good for you.

Are Sports Contracts Swaps Or Not?

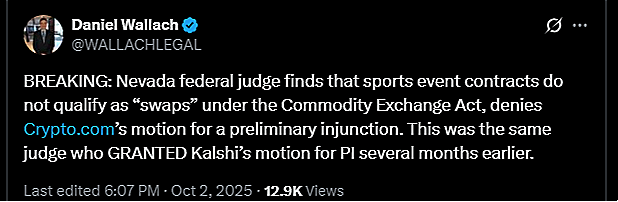

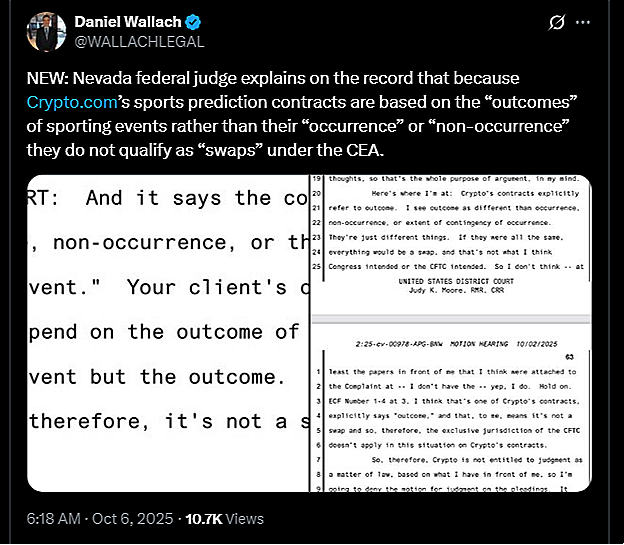

The District Court of Nevada came out with an important ruling last week:

And some more here, again from Dan Wallach:

We will be dissecting the opinion and will put something out in our sister blog Full Court Press soon. Two quick reactions, though:

→ The distinction between outcome and occurrence seems artificial; and

→ One doesn’t even need sports contracts to be swaps for the CFTC to have jurisdiction.

Those two aside, if sports contracts are not swaps, likely the election contracts are not swaps, either. Sports is the biggest prediction market out there, and elections are pretty meaningful, too. If the CFTC lacks jurisdiction, Polymarket can’t possibly be worth $8 billion–not to mention that its recent acquisition may also have been a dud.

And if they are swaps? That’s hardly a lifeline for Polymarket.

Does the Economic Purpose Test Still Have Some Teeth?

If sports contracts are swaps, then the CFTC likely has exclusive jurisdiction. But that raises the next question: Do they involve gaming? That’s one of the prongs in the Special Rule that the CFTC once described as an “obstacle.”

It’s hard to believe that the long-standing societal effort to keep gambling separate from the futures industry, an effort that held sway for over a century, and was still going strong as recently as two years ago–now carries little weight, if any at all. We’ve always believed that “gaming” means “gambling,” and the assessment tool is the economic purpose test. The only court that showed signs of exploring that interpretation seemed poised to reverse the lower court’s ruling, before the CFTC dismissed its appeal.

Yet even if the economic purpose test is dead, Polymarket still isn’t off the hook…

If Gaming Simply Means Games, Then Sports Events Are Still In Play

Even if “gaming” doesn’t mean “gambling,” Kalshi’s position was that the prong still ruled out sports events contracts. They maintained that position all the way through oral argument in the Court of Appeals. The following exchange is not easy to find, but it’s available:

COURT: That supports kind of the CFTC’s view that gaming means gambling because that is something that states and Congress have traditionally wanted to regulate and minimize and might want to regulate here. And gambling is one of the very common, and in some dictionaries, it’s the first definition of gaming. And so I take your point that gambling is broad, and then that might swallow up the whole statute. But if you’re just kind of looking at this as what was Congress’s purpose, it would seem that what Congress’s purpose is more likely that they were concerned about gambling than whether who’s going to win the Super Bowl just as a game?

So, the Court was exploring the idea that gaming means gambling. Not just sports event contracts, but any contract that might be deemed as gambling, including election contracts. (How does one determine what’s gambling and what’s not? The economic purpose test).

Kalshi was trying to make sure the election markets stay alive, so they pushed back:

KALSHI: Well, Your Honor, the legislative history is exclusively about sports when it talks about gaming. So I think there is a reason to believe Congress was particularly concerned at the time it enacted this statute about sports betting and that that was probably what they were getting at with the word gaming… I think it’s pretty clear Congress was not trying to cover the waterfront because we have these markets. They’re supposed to cover something. And if you read gambling in its broadest possible sense, or if you read ‘involve unlawful activity’ in the way the commission wants to read it, you do swallow up everything. (emphasis added)

Our sentiments exactly. They are supposed to cover something. And, at a minimum, they cover sports event contracts. In its pursuit to save its election markets, Kalshi conceded that sports event contracts are out of bounds.

This exchange happened on January 17, 2025. Just a few days later, Kalshi self-certified its sports event contracts. The CFTC didn’t initiate a review, but the issue will be litigated in full at some point. So here’s the question:

If “gaming” doesn’t cover sports games, what does it cover exactly?

We don’t think Kalshi, Polymarket or anybody else has a legitimate answer. And let’s not forget that the District Court in Kalshi vs. CFTC also thought gaming likely covers event contracts related to sporting events:

Applying that definition, event contracts related to any of the sporting events the senator mentioned on the floor could implicate the gaming category.

The judge hedged slightly:

And second, the Court cannot take much from the remarks of one senator to elucidate the meaning of the statute. The D.C. Circuit has warned that “judges must ‘exercise extreme caution’” with such floor exchanges. (internal citations omitted)

…But still concluded the floor exchange could possibly save election contracts, but not sports event contracts:

In fact, if the Court were to take anything from this floor exchange, it would be that the senator would not have intended “gaming” to include elections given the examples offered.

So we have full convergence here. Kalshi, the CFTC, the District Court and the Court of Appeals all agreed that sports event contracts are out of bounds. Yet, here we are with Polymarket almost 10xing its valuation in just three months.

In litigation, what will Polymarket and Kalshi say–other than “the CFTC didn’t take action”? At best, that might mean the proper recipient of scrutiny isn’t Kalshi or Polymarket–it’s the CFTC. But someone has to be on the hook, because the sports event contracts are almost surely contrary to public interest.

Final Thoughts

It’s possible that state-regulated sports gambling survives. Maybe the easiest path is treating sports differently. Congress carved out onions and motion picture box office receipts from the definition of commodity for political reasons–so another politically-motivated carveout might do the trick. Alternatively, the courts may choose to leave the state-regulated sports gambling industry intact.

But if the courts follow the law where it leads? Then, sports gambling is gone entirely–until and unless Congress enacts new legislation. With only 7% of Americans believing sports betting is good for the country, public opinion and existing law may be converging.

Moreover, if sports gambling disappears completely, it may not return for a while. Pick up Gaming Law in a Nutshell, and it becomes clear that America has gone through waves of gambling. Could we be witnessing the end of the third wave?

In sum, the two likely scenarios are (assuming federal jurisdiction is established):

i) State-regulated sports betting is saved; or

ii) No version of sports gambling is spared.

Unfortunately for Polymarket, neither outcome is favorable. Polymarket only wins if the country pivots–erasing a century of congressional intent and precedent, and embracing a world where your Eagles bet and your crypto holdings co-exist on all-in-one platforms that cater to speculative desires, in a reverse Robinhood kind of way (taking from the poor and giving it to the rich).

But even such a radical departure may not be enough. We believe a crisis is a matter of when, not if–and it doesn’t take a genius (or an event contract) to ascertain that prediction markets will be seen as the culprit. Crypto is the other horse in that race.

America doesn’t always get it right before the big bang–but it usually course-corrects afterward. The two major pieces of financial regulation–the securities laws of the 1930s and Dodd-Frank in 2010–were both reactions to financial crises. The first was about stocks and the line blurring between investing and speculation. The second was about derivatives. Now, America gets a 2-in-1 special: Prediction markets and crypto.

That will likely do it. And in the unlikely event that it doesn’t, AI will eventually be sophisticated enough to call out the nonsense accumulating in finance seeping into the judiciary, and repackage it so no one can miss it.

Odds are that America will come to its senses–either through the judiciary before the crisis (one can hope), or congressional action after, or AI realizing its true potential at any time.

Odds are that Shayne Coplan will become a footnote in history–more like the George Graham Rice of the 21st century than a Ben Graham.