Speculation - Type 1 vs. Type 2

With diabetic parallels...

We previously wrote about two types of speculation, but yesterday was the first time we explicitly labeled them, calling them Type 1 and Type 2 speculation. We will use today’s post to elaborate on these concepts as we feel they are rather crucial building blocks toward understanding why the definition of investing has gone haywire. This distinction also lays bare the differences between 20th-century finance and 21st-century finance.

You may recognize the terminology from an entirely different context: health. Diabetes is one of the most important health challenges of our times. As the author whose father is a diabetic can attest, it can be quite limiting and harms the body in multiple ways. (Love you Dad! Stay strong.)

You may or may not realize that not all diabetes are created equal. Type 1 diabetes is believed to be caused by an autoimmune reaction and develops early in life. It’s a type of disease that the patient generally has little to no control over. Type 2 diabetes, on the other hand, develops over the course of many years and is related to lifestyle factors such as being inactive and carrying excess weight. The good news is that one can control it to a large degree, and put it into remission with the right lifestyle choices.

Type 1 speculation and Type 2 speculation have some similarities to this medical dichotomy. Type 1 speculation, even for the self-aware, may be difficult to identify. It inherently involves elements of subjectivity (when estimating the value of a cash-flow-generating asset), and it occurs on a spectrum. It also occurs somewhat naturally in the sense that it is a byproduct of having capital markets that are, net-net, beneficial for the public. As a result, there is only so much the regulator can do to control Type 1 speculation.

Type 2 speculation, on the other hand, is generally not about capital generation. Type 2 diabetics need to know, first and foremost, that what they have is Type 2 (diagnosis) and also that they can manage it fairly well if they are willing to make the right lifestyle choices (treatment). This makes it an informational disclosure issue followed by the willingness of the patient to impose self-discipline. Similarly, when it comes to Type 2 speculation, both the regulators and the market participants have a greater degree of control. With the right regulatory structure, Type 2 speculation can be managed, or even put into remission.

Type 1 Speculation

Remember the simple definition of investing: Investing is akin to buying cheap apple trees. What does “cheap” mean? We dedicated this entire post to elaborating on this concept, but basically, “cheap” is a relative statement that requires comparing price to value. Thus, in true investing, cheap is not a gut feeling or even a comparison to a historical price. There is nothing strange about a stock that was valued at $10 which was priced at $8 a year ago, and the same stock being valued at $2 and the price being $4 today. Indeed, if the only lens one has is prices over time, the stock would appear cheap by historical standards. But to a true investor, the stock was cheap last year ($8 is less than $10, and the 20% discount could potentially be considered as sufficient margin of safety), but it is expensive today because it is trading at twice the value!

If you still want to buy the stock at $4 because you think it will go to $5, then you become a willing speculator and that is your choice; by all means, go for it. As Ben Graham noted in The Intelligent Investor:

Outright speculation is neither illegal, immoral, nor (for most people) fattening to the pocketbook. More than that, some speculation is necessary and unavoidable, for in many common-stock situations there are substantial possibilities of both profit and loss, and the risks therein must be assumed by someone.

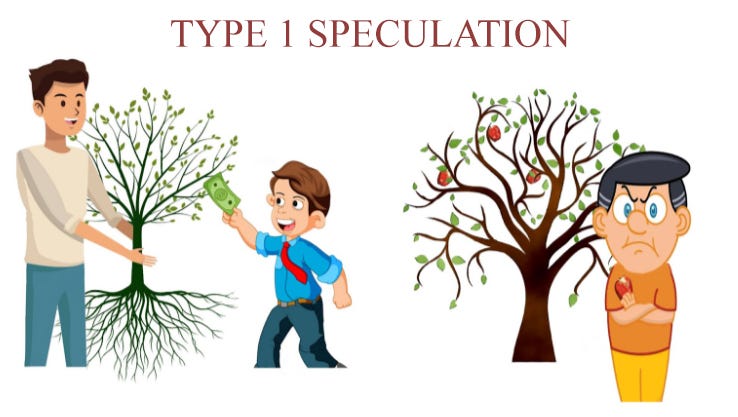

If you intended to be an investor, however, there are two outcomes. It could be this:

Alternatively, you could overpay for a stock and this is probably how you would feel.

What happened here? The individual on the left did buy a cash-flow-generating asset (symbolized by a young apple tree), but the tree did not produce enough apples (relative to the purchase price) which left the buyer disgruntled.

What can the regulators do for these individuals? Not much really because the securities laws mandate the disclosure of all material information, which the buyer, at least in theory, has access to. Is it the government’s responsibility to hold the hand of the buyer and assist with the valuation? That responsibility must fall on the buyer.

Of course, the markets are all connected. It is true that if there are many purchasers in the market paying too high a price for a cash-flow-generating asset, they might overcrowd the other side of the market that are taking opposite positions (by selling, or selling short). That, in turn, might lead to bubbles, which can be described as substantial overpricing of an asset relative to its value. One can characterize the resulting situation as euphoria (.com bubble comes to mind, and more recently the GameStop saga). What can the regulators do in these instances? Again, not that much. As Jay Clayton, former SEC Chair observed:

We regulate disclosure, we regulate trading… one thing that we don’t regulate, directly, … is euphoria.

Should unsophisticated participants not be allowed to access the markets? That is pretty much a non-starter for Jay Clayton, and one might say, it does indeed run counter to fundamental principles that the country is built on:

We do allow direct access to our markets for retail investors, and in those situations, retail investors have the ability to buy and sell as they please. It is a hallmark of American society.

So what to do? According to Jay Clayton, the solution is more educational than regulatory:

We’re trying to do the best we can to educate people about the risk of being in the market, particularly the risk of leverage, the risk of options.

Certainly, leverage and options are important pillars of a comprehensive financial education. What is not happening though, in our view, is a much more fundamental piece that needs to take the front seat in every financial education curriculum - the difference between investing and speculation. This is exactly where we come in.

Before finishing up, Jay Clayton reiterates what might sound like the waving of the white flag to the casual observer:

It is difficult to price euphoria, because you don't know what the level of euphoria is going to be in any particular name.

Yet, this is just a consequence of having free markets. If we want a free market where people can form different opinions based on full and fair disclosure, it is axiomatic that we must sometimes also allow for the possibility that prices will get out of hand at times. Jay Clayton notes:

We’ve generally allowed the public — for First Amendment and other considerations — to have their own views on stocks. The idea that we’re going to regulate retail investor opinion on stocks is a difficult one for people to get their head around.

So, Type 1 speculation is a bit like Type 1 Diabetes, isn’t it? It happens somewhat naturally, as a byproduct of having capital markets, and one can say, it started happening early on when we compare the financial history of America to a human life. Recognizing what’s happening is certainly important, but beyond that, one can exert some control over it, but not a whole lot. In some ways, prices being disconnected from value is precisely what gives the person who is willing to calculate the value an advantage by recognizing the gap between the two.

Type 2 Speculation

Type 2 speculation, on the other hand, is not about paying the wrong price for the “right” asset ( “right” meaning that it generates cash flows). Instead, it is about buying an asset that is not designed to generate cash flows in the first place.

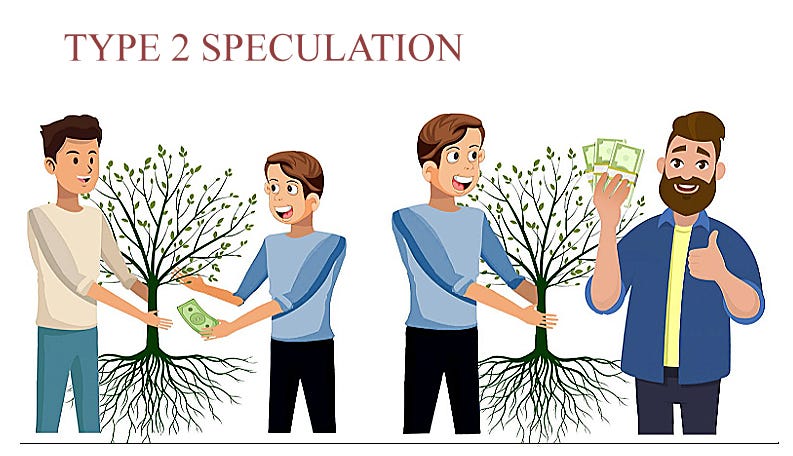

What happens if you do that? Well, there are two possibilities. This is one of the possible outcomes:

You buy an asset that does not generate cash flows, symbolized by the tree. You know quite well that it won’t produce any fruits but you don’t care whether or not it does. As long as you find another buyer who is willing to pay you more than what you paid for it, you’ll make a profit. If you purchased Bitcoin for $10K or less, for example, you are probably well aware that the market has supplied you with many willing buyers like these.

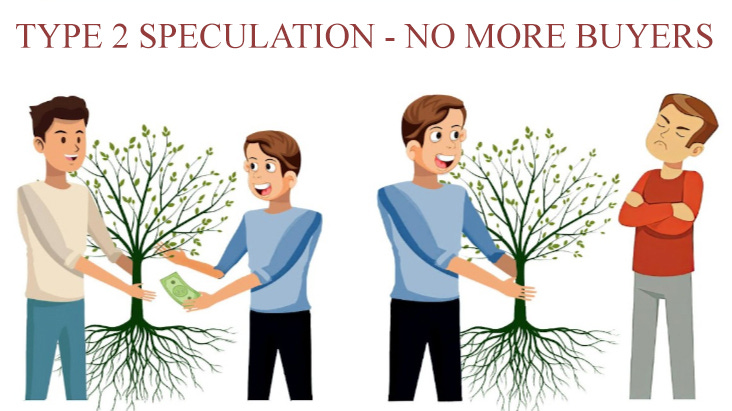

Of course, it is also possible that you may not find that buyer. In which case, you may feel like this:

This may have been the case if you purchased Bitcoin at $60,000 or more. Perhaps the market offered you willing buyers, but you felt it wasn’t enough for a Lambo, so you passed. Or, perhaps, the price started going straight down and never recovered. It may one day, or, it may not because it is pure speculation that a buyer will always be there for a higher price.

Now, you might say, what is the difference? Either way, it’s about buying low and selling high. If I bought Bitcoin at $10,000 or less, you might say, it turned out to be a good investment.

The difference is, and it is a big one, that in the first example above, the buyer actually calculated a value. Then, the buyer compared it to the price and concluded that the asset was cheap relative to its value. The idea is that sooner or later, that value will be recognized by the market, and either you will enjoy the fruits of the tree directly, or you will be able to sell to somebody else who will enjoy the fruits of the tree (or, they will sell to somebody else who will do so, this reasoning applies ad infinitum).

With Bitcoin, you either just got lucky, or you correctly forecasted the animal spirits in the market. So, it may have been luck or skill (one could argue that predicting collective human behavior is a skill), but you did not rely on your skill of estimating its value. The fact that it leads you to the exact place, profits, is not enough to qualify your trade as an investment.

What is a regulator supposed to do in this case, i.e., with Type 2 speculation?

A simplistic view could be that personal liberties trump and retail investors have the ability to buy and sell as they please. Isn’t that what Jay Clayton said, after all?

One can find many posts on X (f/k/a as Twitter) along those lines, like this one:

We have a different take. Personal liberties are given as a right, but society still owes the individuals full and fair disclosure. With Type 2 speculation, retail investors think they are investing, but they are merely speculating. All of them, at any price. When Type 2 speculation is present, the biggest disclosure of all is that the individual is NOT investing! We don’t think the current regulatory path is sustainable, nor will it protect retail investors. How can they be protected if they don’t realize what they are buying? There is a better way.

So, don’t you think Type 2 speculation is a bit like Type 2 Diabetes? For starters, it took a few decades for it to develop, it’s more of a 21st-century finance phenomenon. Further, the “investors” could make a different choice, if they only realized that they are not investing. The regulators need to diagnose the situation and make it clear that being a speculator is not a function of price vs. value anymore, as is the case with Type 1, but rather a function of the asset, if we can call it that. It would be unfathomable to imagine a doctor, who doesn’t disclose to their patients that they have Type 2 diabetes and explain that they can manage it quite well with lifestyle changes. The patient has a choice -should always have a choice- but the doctor has a responsibility to inform the patient about the diagnosis and the consequences of various choices. The financial regulator’s responsibility with Type 2 speculation is no less than the doctor’s.