The Simple Definition of Investing (In Four Words)

Calling all fifth graders and grandmothers

Language is a complex entity, as words can hold different meanings for different individuals. While jargon may be inevitable at times, excessive usage of it can lead to confusion and disconnection with the audience. Therefore, clarity should be prioritized, while ambiguity should be avoided.

The desire for simplicity is often exemplified by the ability to explain a concept in a way that even a young or elderly person can understand. Some individuals may express this as "Explain it to me as if I were ten years old," while others commonly refer to explaining a concept to a fifth or sixth grader. The technique is often attributed to Richard Feynman, an American physicist and co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in physics in 1965. A crucial step in the Feynman Technique involves presenting the topic in a manner that a sixth-grade student can comprehend.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, there is the notion of the “Grandma Test,” which suggests that if you are unable to explain a concept to your grandmother, who may not be well-versed in the latest advancements, then either i) your understanding of the subject is not sufficient, or ii) you haven’t dedicated enough time to refining your message to be concise and clear.

Now, let's consider how this concept can be applied to the definition of investing. When it comes to this topic, Ben Graham, widely regarded as the greatest of all time (GOAT), serves as a prominent figure and was also Warren Buffett's mentor. Let’s recall his definition of investing as presented in his seminal work Security Analysis (Sixth Edition), which he co-authored with David Dodd:

An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and a satisfactory return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.

Fantastic definition, but… Does it pass the fifth-grade test? Can you explain it to your grandmother? With all due respect to Graham, we don’t think so.

Here is our attempt:

Investing is buying cheap apple trees.

Why an apple tree? Well, investing is all about buying an asset that produces something as Warren Buffett explained in this video:

The whole point is that the asset produces “income.” You retain ownership of the asset, and it yields returns (fruit) over a specific period, possibly indefinitely. You have the option to sell the asset at a "profit" if desired, but it is not obligatory. That is the critical point. If a potential buyer emerges who is willing to purchase the asset at a mutually agreeable price, wonderful. The buyer might perceive greater value in the asset's productive capacity or have other motivations for acquiring it. That said, you can choose to hold onto the asset and enjoy the returns (fruit) it produces.

Would you ever buy an apple tree that you know will absolutely not yield any apples whatsoever? Most likely you wouldn’t. After all, what would be the point? So, why would you buy an asset that is guaranteed to never generate any income?

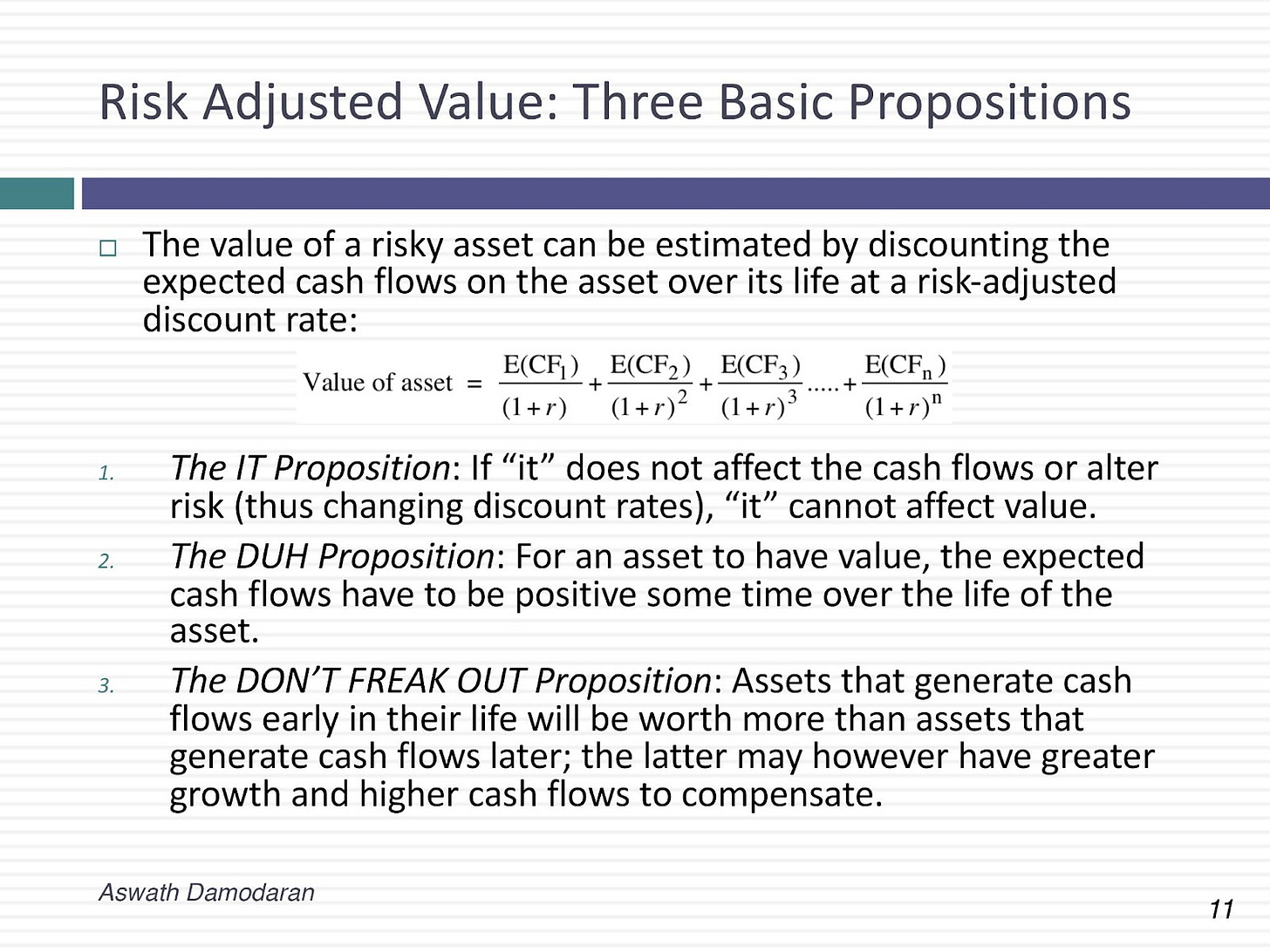

If your initial response is "duh," then you might find it interesting to know that Aswath Damodaran refers to it as the “DUH proposition” in this PDF document. Here is the slide showcasing the “DUH proposition:”

In fact, this knowledge was quite commonplace in finance over 100 years ago! That’s correct, well before the advent of smartphones, computers, modern fax machines, and around the time when cars resembled the ones depicted below:

Photo credit: supercars.net (link to the blog page)

It was a long time ago, and during that period, people didn’t consider investing as anything beyond purchasing an apple tree. Ben Graham himself recounted the times, as described in the passage from the book Benjamin Graham on Value Investing by Janet Lowe (excerpt follows):

When I came down to the Street in 1914, an investment issue was not regarded as speculative, and it wasn’t speculative. Its price was based primarily upon an established dividend. It fluctuated relatively little in ordinary years. And even in years of considerable market and business changes, the price of the investment issues did not go through very wide fluctuations. It was quite possible for the investor, if he wishes, to disregard price changes completely, considering only the soundness and dependability of his dividend return, and let it go at that -- perhaps every now and then subjecting his issue to a prudent scrutiny.

Is this common knowledge now? If you belong to the “duh” camp, you might assume that it still is. However, that is not the case. If you don’t believe us, take a look at our June posts and see if you think we’re mistaken. There are significant segments of the market, or perhaps the particularly vocal segments, that have strayed from the narrower definition of investing.

But why has this backward progression occurred? We've advanced from the cars depicted above to AI, yet it seems that finance has regressed. Well, let us just say that we are not the first ones to make this observation. This quote from James Grant, an American writer specializing in history and finance, beautifully encapsulates the sentiment:

Progress is cumulative in science and engineering, but cyclical in finance.

Indeed, this statement rings true. You can consider us as a collective striving to transform finance into a discipline that more resembles science – a field that progresses steadily forward rather than moving in circles, and we believe that the job starts, first and foremost, by building consensus on definitions.

Hopefully our perspective on the meaning of “apples” is now clear. An investor buys an apple tree for the purpose of obtaining apples, but the question arises: at what price? This is where the concept of “cheapness” comes into play, which we will delve into in our discussion tomorrow.