Crypto Is On a Roll

Part I: But is America about to trip over its own proposed legislation?

There’s a pesky little term that just won’t go away: “investment contract.” It’s resilient. It’s powerful.

And quite possibly, it’s the only thing standing between crypto and a bleak future for America.

So what happens when you’ve got this shiny new thing–crypto–but a powerful, century-old statute looms large? You try to make sure the old, powerful thing does not apply to your new, shiny toy. You couch it as responsible innovation. But in reality, you’re limiting the amazing possibilities that innovation could unlock.

We’ve said this before, and we’ll say it again: We are not anti-crypto. We are pro-innovation. If blockchain technology helps us do things better, faster, and more efficiently, great. Why would we oppose that? And if the technology works better with native cryptotokens, that just means that the tokens are part of the innovation.

But for innovation to reach its full potential:

→ The best technology has to win.

→ For the best technology to win, speculation must shift away from coins unmoored from real utility.

→ That shift only happens if America agrees: One cannot invest in crypto.

→ And we only get there if we establish consensus on what it means to “invest.”

→ If we fail to do that in short order, some version of RFIA may pass, severing the link between crypto and the term “investment contract.” The chain breaks. Innovation stalls.

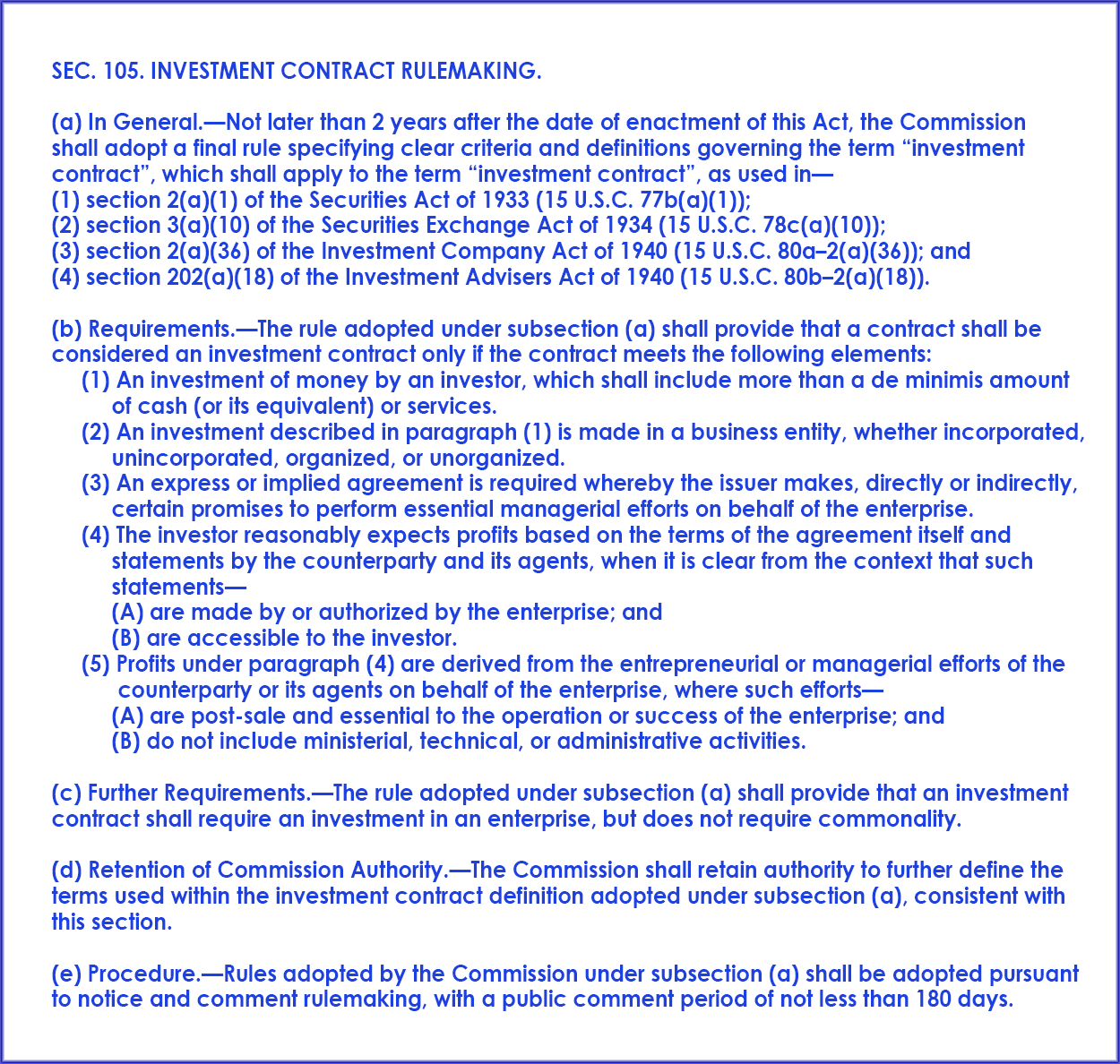

Let’s look at what RFIA (PDF) actually says about investment contracts:

A full legal breakdown would be better suited for our sister blog, Full Court Press. But, here’s the core takeaway: RFIA cabins the definition of “investment contract” to business entities. If you’re investing in a business, the term still applies. If you’re “investing” in crypto, RFIA may sever that link.

Let’s test this against Bitcoin:

Investment of money? ✅

Business entity? ❌

Agreement/Issuer? ❌ (You buy it on an exchange. No issuer, no promises.)

Statements? ❌ (Saylor and Wood speak often and likely influence the price, but they’re not the enterprise)

Entrepreneurial/Managerial efforts? ❌ (Profits come from transactions where the trader finds a buyer willing to pay more for the asset, not enterprise performance)

Critically, as you can see, four of the five points in RFIA’s definition of an investment contract don’t even apply to Bitcoin.

Maybe it’s not a surprise–the SEC, even under Gensler, maintained that Bitcoin isn’t a security. Paul Atkins, the current SEC Chairman, recently stated that most tokens likely aren't securities either.

We’ve disagreed with the SEC on this before, and we still do. Because the real question isn’t whether crypto passes the Howey test. The real question is:

Do crypto purchasers need the protection of the securities laws?

The goal is investor protection–not exemption. And yes, there’s a valid reading of Howey that would classify most tokens as securities.

But if we’re right about the definition of investing–and one cannot invest in crypto–then the entire framework collapses. Here’s how:

If crypto isn’t an investment, the government must say so. Otherwise, people are being misled.

If RFIA passes, one of the most important avenues for investor relief disappears.

That’s the opposite of what Congress intended in 1933 and 1934.

It’s also contrary to the SEC’s mission of protecting investors.

And the harm isn’t just individual–it’s systemic.

If crypto gets a more favorable regime than stocks, capital flows toward tokens and away from businesses. That’s not market efficiency, that’s market distortion.

RFIA isn’t even good for crypto itself. Bill Hughes flagged the tension between “money crypto” and “tech crypto.” But he missed the deeper truth: The relationship isn’t symbiotic–it’s adversarial.

When Money crypto dominates, attention flows to tokens with marketing muscle and hype, not technological merit.

That’s terrible for innovation, bad for developers, bad for purists and ultimately bad for most of the American public.

So yes, quite a bit rides on how we define “investing.”

If you’re rooting for the best technology, RFIA is bad for you.

If you’re building that technology, RFIA is bad for you.

If you’re a startup that aims to cure cancer, RFIA is bad for you.

If you’re a cancer survivor–or know a survivor–RFIA is bad for you.

If you run a crypto exchange, RFIA is good for you.

If you own Bitcoin, RFIA might be good for you–if you exit at the right time. If you don’t, RFIA is bad for you.

If you dabble or leverage on memecoins, RFIA is most certainly bad for you–because when you lose your money, the securities laws won’t be there to help you.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. RFIA doesn’t just redefine a legal term—it reshapes the playing field for innovation, investment, and public protection. If we get the definition of “investing” wrong, we don’t just misclassify crypto—we misallocate capital, mislead consumers, and misfire on the very goals our securities laws were designed to uphold.

In future posts, we’ll continue to talk about why the definition of investing is crucial. From regulatory policies to retirement plans, this one word just happens to impact everything. We’ll show you how deep the rabbit hole goes. Will you join us on the journey?