Crypto Is On a Roll

Part IV: Speculation disguised as investing: Disclosure, mislabeling, and the SEC’s identity crisis

Unsurprisingly, as we near the end of this series, crypto remains a hot topic. Just watch this video clip of Eric Trump declaring that crypto solves all the problems of modern day finance:

Does it? Sure, the financial system has inefficiencies, and blockchain technology offers promise, but for most Americans, crypto isn’t a problem-solving tool, it’s a speculative vehicle. A recent survey found that 93% of participants are in it to make money.

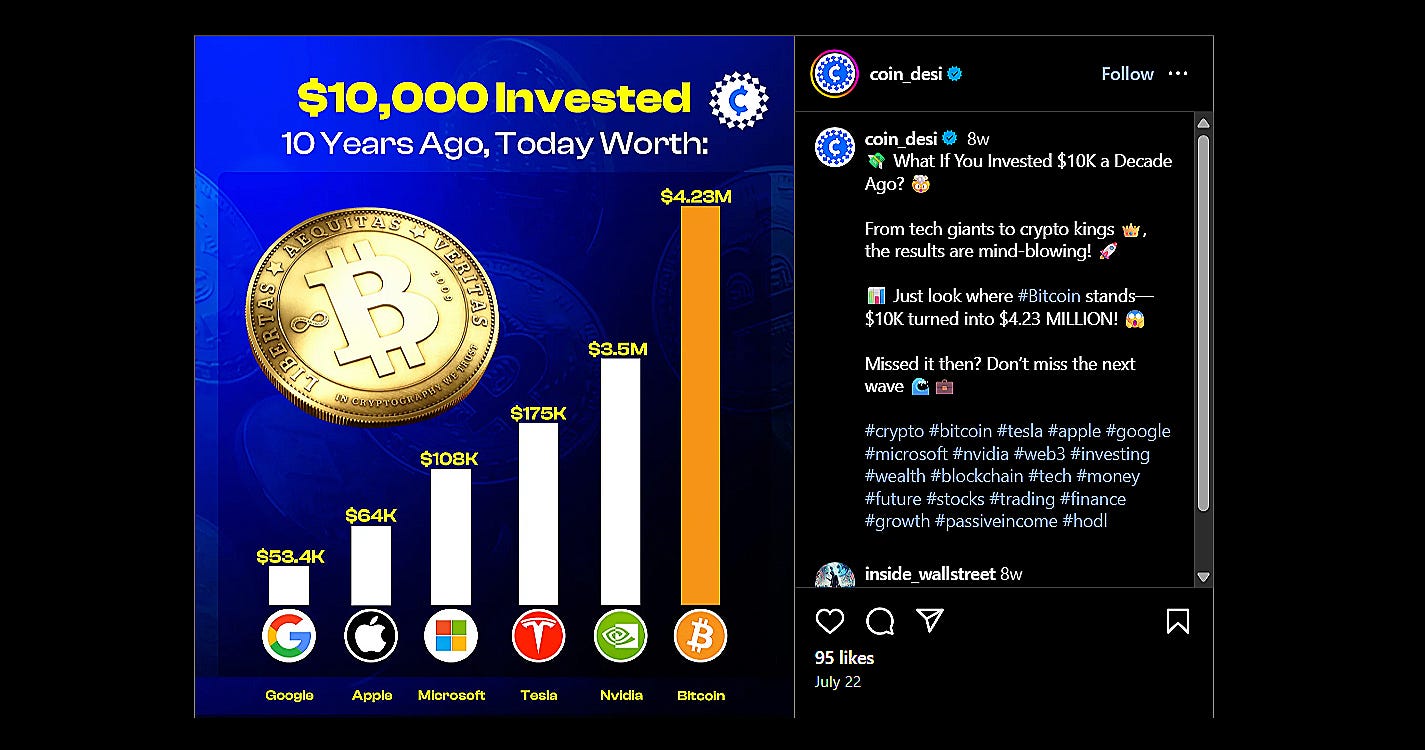

Inherently, that’s not a bad thing. The problem is that most people don’t realize they’re speculating. Posts like this one have become routine on social media:

Comparing crypto to stocks is comparing apples to oranges. Why? Because it’s a comparison between (potential) investing and speculation. We’ve discussed perceived equivalence before. The fallacy lies in comparing returns without comparing the fundamentals.

So who’s supposed to clarify the difference? Ideally, the regulator whose mission is to protect investors: the SEC. Let’s revisit the two types of protection the public needs:

Full and Fair Disclosure on Cash-Flow-Generating Opportunities

This protection exists because, without it, investors can’t make informed decisions.

→ Equity in companies is a claim on future cash flows.

→ Cash flows depend on company performance.

→ Investing requires estimating the value of those cash flows.

→ Without proper disclosure, estimation is difficult. The public would likely overestimate the true value, and thus end up overpaying, which would mean they are speculating, not investing.

It took a serious crisis–The Great Depression–for lawmakers to realize this--one congressional finding revealed that half of the stocks were worthless. Eventually Congress got there. Regulatory filings may be TLDR, but they exist for those who want to read them.

This regime has worked reasonably well for a century. Whether quarterly disclosures are optimal is still debated. Some argue for semiannual reporting to reduce Wall Street pressure. Perhaps the solution isn’t less reporting, it’s smarter reporting. At minimum, most investors probably still want to see quarterly financials.

There’s also chatter about running equity markets 24/7, using crypto as a blueprint. Extending trading hours in equity markets would likely increase speculation and reduce investing. Is that a good thing? We doubt it.Full and Fair Disclosure on Trading Activity Itself

Critics say the securities laws are outdated for 21st-century finance. But let’s set aside statutory language and focus on intent: protecting investors.

In the 20th century, investors focused on cash-flow-generating assets such as stocks and bonds. Disclosure centered on material information affecting the cash flows.

In the 21st century, participants are “investing” in cryptocurrencies, NFTs, art and generally anything that trades. The issue isn’t the trading itself, but the framing. This isn’t a missing information problem. It’s a false advertising problem.

Fix the messaging. Be truthful. Tell people they are speculating, not investing. Let the chips fall where they may.

Why does this matter?

→ Culturally, “investing” evokes prudence and safety.

→ But safety isn’t guaranteed–it’s earned.

→ Disclosures level the playing field, but investors still have to work.

→ That work involves valuing cash flows and comparing price to value.

→ Crypto has no cash flows. You can’t value it.

→ Safety comes from buying cheap and expecting future cash flows.

→ With crypto, there’s no “cheap,” just demand. When buyers vanish, there’s nothing left!

→ Many believe Bitcoin can’t go wrong. “Number go up,” they say. Maybe. But that’s not safety. That’s guessing future speculative demand.

If the SEC had simply told people what they needed to hear–not what they wanted to hear–we wouldn’t have these issues. Instead, on July 31, 2025, the SEC launched Project Crypto (there is also a short video here) with SEC Chair Paul Atkins opening with:

Today, I would like to discuss what Commissioner Hester Peirce and I are calling “Project Crypto,” which will be the SEC’s north star in aiding President Trump in his historic efforts to make America the “crypto capital of the world.”

We get it. The desire to lead in crypto is undeniable. But it can't happen without consensus on what investing truly means.

Capital formation is at the heart of the SEC’s mission, yet for too long the SEC ignored market demands for choice and disincentivized crypto-based capital raising. As a result, crypto markets pivoted away from offering crypto assets and deprived investors of the opportunity to use this technology to contribute to productive economic enterprises.

Alternative capital formation is fine–if the rules are clear. But the real problem isn’t crypto-based fundraising, it’s crypto purchases themselves. Who’s protecting those buyers?

In theory, the statute does–by defining “security” to include “investment contracts,” a term shaped by decades of case law, starting with SEC v. Howey, the seminal Supreme Court case. If crypto assets are securities, investor protections apply.

But the SEC appears to be headed in the opposite direction:

Despite what the SEC has said in the past, most crypto assets are not securities. But confusion over the application of the “Howey test” has led some innovators to prophylactically treat all crypto assets as such.

This statement may go down as one of the most consequential, and not in a good way. Yes, the Biden-era SEC struggled with Howey, but so does the Trump-era SEC. There’s an alternative reading of Howey–one we’re trying to advance–that concludes most crypto assets are securities. Flip Chair Atkins’s conclusion, and everything else flips with it.

Even then, the solution isn’t more quarterly reports or expansive administrative burdens. It’s much simpler: A label. A label that follows all speculative products and tells the world what they are: Speculative assets.

This isn’t exactly a novel solution. A similar system existed a century ago (see section III.D of this amicus brief)–misapplied, but precedent nonetheless. Another example akin to this solution is the Surgeon General’s warning on packs of cigarettes. Rather than banning cigarettes completely, a label was applied and the decision was left to the American public to heed the warning.

If the SEC doesn’t get there, maybe Congress will. Maybe we’ll agree that in 21st-century finance, the SEC’s role is more akin to the FDA or USDA–primarily a label regulator, not an information disclosure machine.

The approach must evolve but the mission does not change: Protect investors.

And if it doesn’t? Well, then we’re all on our own again–ripe for being taken advantage of just as the public was before the Great Depression. Congress and the SEC working together would produce the best outcome for society, but you can still largely fend for yourself if they fall short of implementing a mass solution. You are the hero you need. Just know what game you’re playing and who you’re playing against.

When it comes to crypto, you’re speculating, not investing. Trade accordingly.