Crypto Is On a Roll

Part II: Intrinsic value, gold, and the story of Bitcoin

In Part I of our “Crypto Is on a Roll” series, we explored the regulatory landscape shaping digital assets, with a particular focus on the Responsible Financial Innovation Act (RFIA). We argued that crypto’s future hinges not on hype, but on utility—and that legislators must stop editing the story to fit a narrative. If you missed that post, we recommend starting with our prelude post then continuing to Part I. Part II picks up where we left off, shifting from policy to finance and psychology: What does it mean for an asset to have value, and why do traders continue to believe in Bitcoin despite its lack of intrinsic value?

We’re not in the prediction business and certainly won’t claim that Bitcoin will sink to $200 before it hits $200,000. But Ken Rogoff, a well-known Harvard economist, did make that mistake back in 2018:

That prediction did not age well. Rogoff recently posted a self-assessment:

Pompliano was all over Rogoff on X:

But the joke may actually be on Pompliano. Rogoff understands Bitcoin. His original thesis wasn’t rooted in ignorance–it was grounded in the idea that Bitcoin lacks intrinsic value:

But economists (including me) who have worked on this kind of problem for five decades have found that price bubbles surrounding intrinsically worthless assets must eventually burst.

Rogoff’s mistake wasn’t analytical–it was cultural. He failed to anticipate that most investors no longer care about intrinsic value (and, as a result, stop being investors) or simply don’t understand its true meaning. Investing is hard. Speculation is easier. And most people choose easy.

Pompliano, of course, rejects the concept of intrinsic value altogether.

So, was Rogoff right? Not entirely. He gestured at gold, but didn’t dwell—missing an opportunity to more sharply delineate the contrast between gold and Bitcoin despite both being non-income-generating assets. We’d also argue he misuses the term “bubble,” but that’s another issue altogether.

To his credit, Rogoff did point out that gold has industrial uses. True, but none of those uses confer intrinsic value. Gold, standing alone, does nothing. That’s why Warren Buffett is not a fan. As long as gold is in demand, as an industrial input or otherwise, it will retain value. But it can’t be valued. That subtle distinction continues to perplex even seasoned economists.

Perhaps Rogoff believes gold’s intrinsic value is also zero, but that’s not clear from the Guardian article. Where Rogoff is more convincing is in framing gold as a commodity rather than an asset. We agree. Gold is less a story (though it does have one) and more a real input to production–wrapped in narrative. There’s something tangible underneath (though it certainly isn’t cash flows), and the story adds a shiny veneer. The fact that gold returned more than inflation but less than S&P 500 over the last 60 years supports this view.

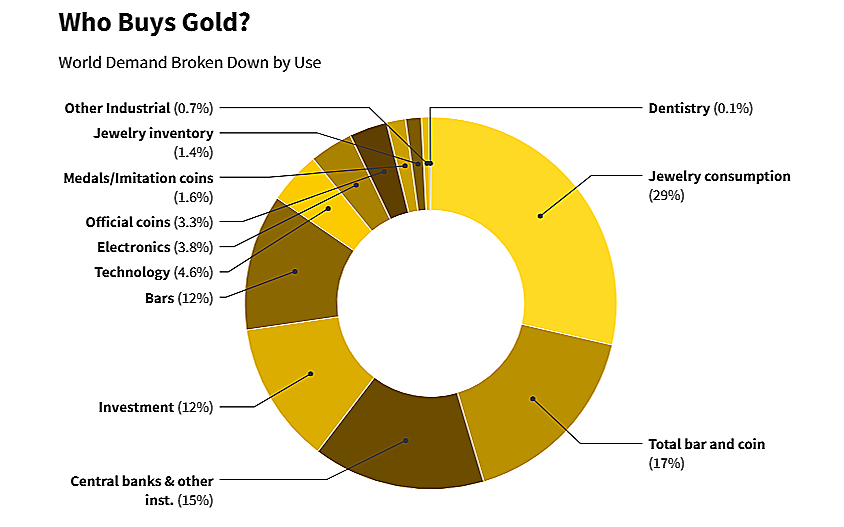

So how much of gold’s value is derived from industrial use vs. “investment” demand? According to Investopedia, citing from the World Gold Council data, only 12% of gold purchases are for “investment” motives.

(Image courtesy of Investopedia)

That feels low, but the data is the data. If accurate, gold’s price is more utility-driven than narrative-driven.

Now compare that to Bitcoin. One survey found that 93% of Bitcoin purchases are driven by investment motives. Bitcoin, then, is almost entirely a story; a shiny wrapper with little underneath. Call it digital gold if you like, but the data shows people buy gold and Bitcoin for very different reasons.

Bitcoin’s intrinsic value is zero, just like gold. But gold’s floor value, by virtue of its commodity status, is much closer to its market price. Bitcoin’s floor value probably isn’t zero, as Rogoff concedes, but it’s far more decoupled from its actual price.

So what does that mean for Bitcoin’s future? Is it doomed? Not necessarily. Bitcoin is a story, it will last as long as people believe in it. But its price will always remain vulnerable to how that story unfolds. If Bitcoin can evolve into a true digital gold–not just by branding, but through actual use–it may avoid the fate Rogoff predicts.

This brings us back to RFIA–in its current form, Bitcoin’s dominance isn’t threatened—but the survival of utility-driven tokens is. True innovation requires that all token assets be allowed to compete on merit, not legacy or narrative. If America wants to foster real technological progress, it must act like a responsible editor confronting a seductive but flawed manuscript: kill the story.

Exempting crypto from securities laws by discarding the “investment contract” standard does the opposite–it embellishes the story.

Bottom line: Let the tokens compete on utility, not hype. And there’s only one way to do that: Establishing consensus on the definition of investing.

In Part III we will dive into the Digital Asset Report, again, through the lens of definitions.