Investing vs. Speculation - The “Spectrum" Mindset

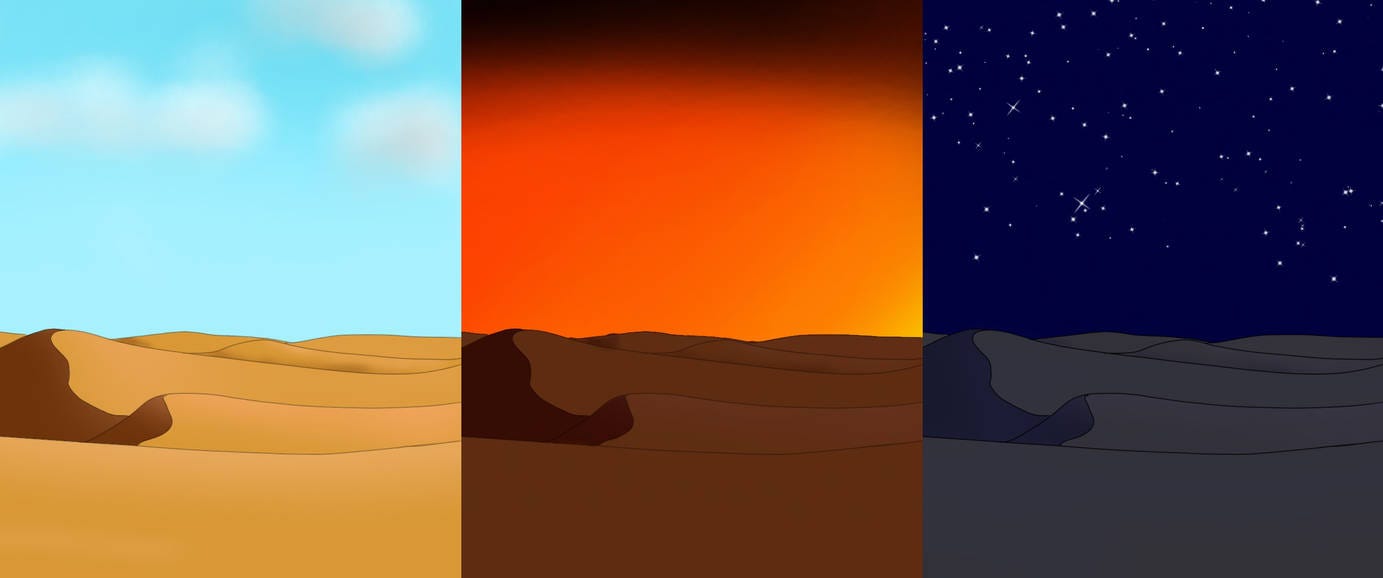

Part I - Day, sunset and night

Yesterday, we discussed the meaning of “cheap” using an illustrative example. However, it’s very important to note that no simple example can fully mimic real-life scenarios. For instance, we purposely overlooked taxes and transaction costs. Further, the interest rate we assumed was 10%, which was chosen for ease of calculation but is considerably higher than the current rates you would receive at your local bank.

Nevertheless, the most crucial assumption that we made was that there was no uncertainty with respect to the return on the asset. In our example, the apple tree was guaranteed to produce 100 apples exactly one year from now, valued at $1 per apple (the prevailing market price), resulting in a total worth of $100. This allowed the buyer to have complete knowledge of what they would receive.

However, this certainty is rarely found in real-life situations. With fixed income instruments, there is certainty about the achievable return, such as a fixed interest rate of 5% on the amount lent. However, there is still a risk that the counterparty might default and not repay the principal and/or interest. Credit ratings and credit scores, applicable to corporate and individual lending, respectively, are meant to assist the lender in assessing this risk.

Stocks pose an even greater challenge. The value of stocks is not known with certainty; they can only be estimated. Although laws require the disclosure of information to ensure transparency between the promoter and the buyer, as a potential investor you still need to conduct an estimation of value exercise.

The concept of the margin of safety is precisely relevant in these situations.

Investing is all about comparing price to value. The challenge is that the former is certain, but the latter is not. While the price is known, the value of the asset will always be an estimation. This contrast necessitates the consideration of a margin of safety. Merely having a price below the estimated value is insufficient to classify a trade as an investment. Although there may be some level of safety, there is no room for error. To truly qualify as an investment, the price should be significantly lower than the estimated value, providing a much greater margin of safety.

Understanding the distinction between investment and speculation is of utmost importance. Many individuals tend to evaluate their investment portfolios by examining the returns and, often retrospectively, conclude whether their investments were good or bad. However, the dominant viewpoint in the early 20th century, notably Ben Graham’s perspective was substantially different. Investing and speculation can be envisioned as existing along a spectrum, with investing at one end and speculation at the other. We discussed this concept in our conversation yesterday:

We suspect that the common perception among most people is that investing resembles a report card, encompassing both good and bad grades. However, a more accurate depiction would liken investing and speculation to day and night, with sunset serving as the transitional phase.

Visualizing the progression from day to night, with the sunset serving as the transitional phase, can help us grasp this concept:

Image credit: Lionzz1 on Deviant Art. Link to image.

We believe that the mental image of day, sunset and night as representations of an investment, speculative investing and outright speculation may be helpful in understanding the distinction between these concepts in the world of finance.

It’s worth emphasizing that investing is not inherently superior to speculation, just as day is not inherently superior to night. They are simply different. During the day you might choose to go out for a run, but at night you would only do so if there is sufficient lighting that simulates daytime conditions. Otherwise, it would be unwise to run in the dark. Similarly, if your objective is safety, why would you engage in speculation?

There is nothing wrong with speculating or investing as long as the two are not confused with each other. We share sentiments with Benjamin Graham when he said in The Intelligent Investor:

Outright speculation is neither illegal, immoral nor (for most people) fattening to the pocketbook. More than that, some speculation is necessary and unavoidable, for in many common-stock situations there are substantial possibilities of both profit and loss, and the risks therein must be assumed by someone.

Graham's emphasis was on ensuring individuals are aware of what they are doing and making informed choices:

There is intelligent speculation as there is intelligent investing. But there are many ways in which speculation may be unintelligent. Of these, the foremost are:

speculating when you think you are investing;

speculating seriously instead of as a pastime, when you lack proper knowledge and skill for it; and

risking more money in speculation than you can afford to lose.

Therefore, with each purchase decision, it is very important to ask yourself: Are you engaging in investing? If not, are you willingly speculating with full awareness of the risks involved? It’s crucial to understand this distinction and make informed decisions based on your objectives, knowledge and risk tolerance.