The Simple Definition of Investing - What Does “Cheap” Mean?

Investing used to be about safety. Not anymore.

Investing revolves around cash flows, or in simpler terms, we can call them apples so it would easily pass the grandma test. Yesterday’s post focused precisely on this concept.

Today, our focus shifts to the second key aspect of investing: price. Let’s delve into a thought experiment to illustrate this idea. Consider the following parameters (we’ll overlook real-life complexities such as taxes and transaction costs):

You decide to buy a grafted seedling - an apple tree for the sake of simplicity - that will yield apples in one year’s time. (Growing an apple tree from seed could take anywhere from 7-10 years before the first fruit is harvested.)

This particular apple tree is special because it guarantees the production of 100 apples per year, but for a single year only. (Ordinarily, a healthy apple tree can bear fruit for up to 50 years).

You have the option to sell each apple for $1 at the local farmers market, and you are guaranteed to sell all of the apples.

The Interest rates on savings accounts stand at 10%, which is paid at the end of the year, coinciding with the apple tree’s growth.

Now, the question arises: How much would you be willing to pay for the apple tree? What price is cheap enough?

Ultimately the solution boils down to comparing two alternatives. If you choose to buy the apple tree, you will own 100 apples. Since each apple will sell for $1.00, your total revenue will be $100. Initially, you might think, “I will buy the apple tree as long as the cost is below $100.”

However, there’s a catch! Remember, the apple tree does not bear fruit immediately. You must spend your money today to acquire the apple tree, but the harvest and sale of the fruit will only occur after a year of waiting.

If you opt not to buy the apple tree, what alternatives do you have? While one option would be to keep your money under your pillow, that is highly unlikely (unless you have trust concerns about the bank, which raises a separate issue). A more practical alternative is to put your money to good use by depositing it at your local bank and earning interest. In this case, your opportunity cost encompasses not only the money spent to buy the apple tree, but also the potential interest you would forgo.

Let’s consider a scenario where the apple tree seller quotes you a price of $90. Performing a quick calculation, you realize you can take the $90 to the bank, in which case you will achieve a balance of $99 by the end of the year (the principal amount of $90 + 10% interest on your principal). However, if you choose the apple tree, it will yield $100 of revenue. Thus, opting for the apple tree proves more advantageous.

If $90 is a reasonable price, then $80 would be more favorable. What about $70? It becomes even more desirable. If the math works out for $90, it will work out for any price less than $90. At $90 the apple tree is reasonably priced, and as the purchase price decreases, it increasingly becomes a better investment.

Let’s examine the scenario where the price of the apple tree is set at $91? If you choose to pay that amount, you will receive the apple tree. By paying $91 today, you will receive $100 next year when you harvest and sell the apples at the farmer’s market. At first glance, this might sound like a good deal.

However, the perspective changes once you consider the alternative. Recall that by depositing your money into a savings account you could earn a 10% interest rate. In this case, 10% of $91 is $9.10. Adding the principal and the interest, you would net $100.10. Now, by simply collecting the interest, you end up in a better financial position.

If $91 is an unreasonable price, then $100 would be less favorable. What about $110? It becomes even less desirable. If the math does not work out for $91, it will not work out for any price more than $91. At $91 the apple tree is unreasonably priced, and as the purchase price increases, it increasingly becomes a worse investment.

We would like to draw your attention to the paragraph above and acknowledge that an issue has arisen in this particular instance. Specifically, a commonly used writing shortcut, which is central to this whole discussion, has failed miserably here.

What do we mean by this? Allow us to explain how we constructed the aforementioned paragraph. We essentially copied and pasted the paragraph that starts with “If $90 is a reasonable price, then $80 would be more favorable.” From there, we proceeded to modify the numbers and adjectives. It was a process that looked like this:

$90 → $91

Reasonable → unreasonable

$80 → $100

More favorable → less favorable

…

…

…

Better investment → Worse investment

Our approach may initially appear harmless, after all, we were just going in the opposite direction, but the issue arose in the final step, and that’s when everything went awry.

An effective way to describe the problem surrounding the significant expansion of the word investing from its original meaning is as follows:

We suspect that the common perception among most people is that

investing resembles a report card, encompassing both good and bad grades.

However, a more accurate depiction would liken investing and speculation

to day and night, with sunset serving as the transitional phase.

Under the first interpretation, several points hold true:

Everything falls under the category of investing, rendering the term “speculation” unnecessary.

A trade is evaluated on its outcome rather than the process. If a trade yields a 200% return, it is considered a very successful investment, regardless of what process was followed. This is akin to the student wanting to receive a good grade, rather than mastering the subject.

There is a possibility of losing the entire principal, which can be likened to receiving a failing grade (F).

Under the second interpretation, which we are promoting, several points hold true:

The emphasis is not on the outcome but on the process itself. By following the right approach, one may not become instantly wealthy, and one will not necessarily be successful in every single trade, either, but it is possible to accumulate significant wealth over a lifetime, as exemplified by the successes of investors like Warren Buffett.

Investing and speculation exist on a spectrum. As the price of an asset becomes excessively high (relative to its intrinsic value), it transitions from the realm of investing to speculation.

Within this spectrum, there are intermediate zones where the boundaries between different characterizations blend. In finance, we refer to this zone as speculative investing, which occurs when the price of an asset is relatively close to its intrinsic value. Just as the day turns to night, with sunset being the transitional phase in between, investing turns to speculation with speculative investing being the transitional phase in between.

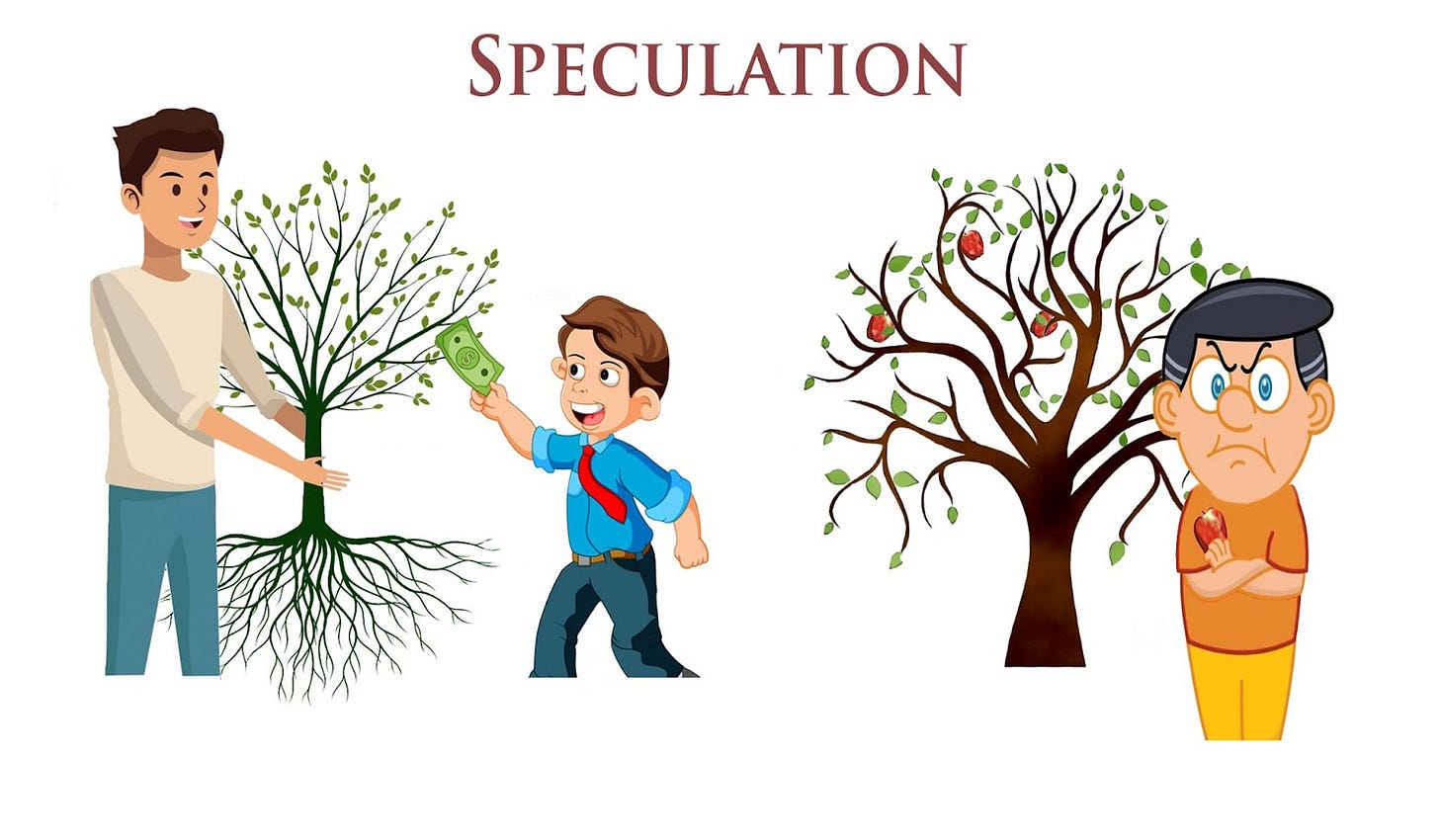

Now, allow us to provide you with another visual representation that depicts speculation within the context of assets generating cash flows:

In the visual representation above, the left panel represents the initial stage, which involves buying an apple tree. As you may notice, it remains unchanged from the picture we used yesterday. However, you will notice the right panel is significantly different. In this case, the amount of fruit harvested is not sufficient when compared to the price paid for the investment.

Allow us to reiterate the significance of this concept:

When the price of a purchase becomes excessively high, it does not simply transform a good investment into a bad one. Instead, it signifies a shift from an investment into speculation. You have essentially crossed the line, transitioning to the other side of the spectrum.

As we mentioned yesterday, the distinction between investment and speculation, based on the concept of price and value, was well recognized even in 1914. It is disheartening to observe that over time, this crucial differentiation has been largely overlooked or forgotten in many instances. However, acknowledging and understanding this distinction remains of utmost importance in navigating the world of finance and making informed investment decisions. For example:

In recent years, crypto has been growing in popularity, with many people treating it as an investment opportunity. But remember, if you decide to invest in crypto then you should be prepared to lose all the money you have invested.

This is just wrong. If we should be prepared to lose all the money we have “invested”, it indicates that we are speculating, rather than investing. While we can opt for speculation, labeling it as investing would be misleading, to say the least.

We find it unfortunate that this perspective does not originate from an anonymous internet writer but from a reputable financial regulatory body, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), based in the United Kingdom!

The FCA continues:

Some cryptoassets appeal to investors based on the ethos of the developers and the use case for the token itself, while other investors may simply be speculating on the price history and volatility of the crypto.

The first part of the sentence accurately identifies the dichotomy between consumption-oriented use and the “investment” aspect of crypto which presents a significant regulatory challenge.

However, the second half of the sentence raises a concern. With all due respect, this seems to be a step backward in the field of finance. Investors typically engage in investing, while speculators speculate. While it is possible for individuals to be investors in some trades and speculators in others, in such cases, they are no longer investing but rather speculating. Replacing the word “investor” in the sentence above with “trader” would provide a more accurate representation of the intended meaning.

We have pointed out a common frustration, which happens to be our number one pet peeve: the misuse of language in the realm of investing. Investing, as it is supposed to be, should not carry an inherent level of danger. By turning out attention to the right sources, this observation becomes rather obvious. It is worth recalling Graham’s definition of investing.

An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and a satisfactory return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative. (emphasis added)

The following observation comes from Howard Marks, co-founder of Oaktree Capital Management and a contributor to Security Analysis (6th Edition - p. 127):

Today people attach the word “investment” to anything purchased for the purpose of financial gain—as opposed to something bought for use or consumption. People invest today in not just stocks and bonds but also in jewelry, vacation-home timeshares, collectibles, and art. But 75 years ago, investing meant the purchase of financial assets that by their intrinsic nature satisfied the requirements of conservatism, prudence, and, above all, safety. (emphasis added)

Walter Schloss (American investor and another Graham disciple) on Ben Graham (excerpt from Benjamin Graham on Value Investing by Janet Lowe - p. 107):

Ben’s emphasis was on protecting his expectations of profit with minimum risk. (emphasis added)

Another excerpt from Benjamin Graham on Value Investing by Janet Lowe (p. 134):

“Confronted with a challenge to distill the secret of sound investment into three words, we venture the motto ‘Margin of Safety’,” Ben wrote.

“Forty-two years after reading that,” Buffett said in one of his annual reports, “I still think those are the right three words. The failure of investors to heed this simple message caused them staggering losses as the 1990’s began.” (footnote references omitted)

One can perhaps raise a valid point about Ben Graham’s usage of the adjective “sound” when qualifying the term investment. It is also true that the title of his seminal book, The Intelligent Investor, perhaps implies the existence of unintelligent, or bad investing. While disregarding Graham’s entire body of work in one fell swoop based on a couple of potentially misleading qualifiers may be an option for some, we refuse to do that. Delving into his writings reveals a clear understanding of his position.

If you need further affirmation from Graham himself, his words, as always, emphasize the distinction between investing and speculation (PDF):

The title of this seminar - ”The Renaissance of Value” - implies that the concept of value had previously been in eclipse in Wall Street. This eclipse may be identified with the virtual disappearance of the once well-established distinction between investment and speculation. In the last decade everyone became an investor including buyers of stock options and odd-lot short-sellers. In my own thinking, the concept of value, along with that margin of safety, has always been at the heart of true investment, while price expectations have been at the center of speculation. (emphasis added)

Indeed, the “margin of safety” concept corresponds to what can be referred to as buying assets cheaply in our simple definition of investing. Similarly, the “concept of value” aligns with the idea of investing in assets that produce something, in our definition, the “apple trees.”

Benjamin Graham is basically saying: At some point, everybody agreed investing is buying cheap apple trees. Not anymore.