The Speculative Investing Fallacy

Part III - What Is Speculative Investing, Anyway?

One leading authority from a century ago genuinely believed common stocks were not investments. It took decades and a charismatic Ben Graham to set the record straight and deliver an important message to the masses: Common stocks are investments, but only sometimes.

This begs the question. What does sometimes mean? It means that the stock has to be cheap enough.

What does “cheap enough” mean? Cheap relative to what?

We covered “cheap enough” in detail in a previous post, but basically, it means cheap relative to the one’s value estimate of the stock.

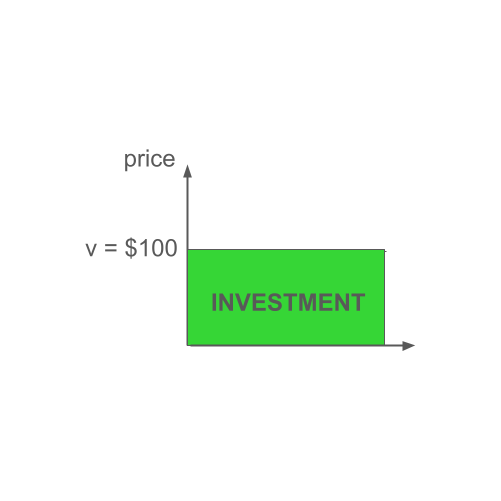

So, if you knew that the value of an asset is $100, surely you would pay anything below $100 right? Anything below that amount would be investing as it is guaranteed return at zero risk. The trade would look like this:

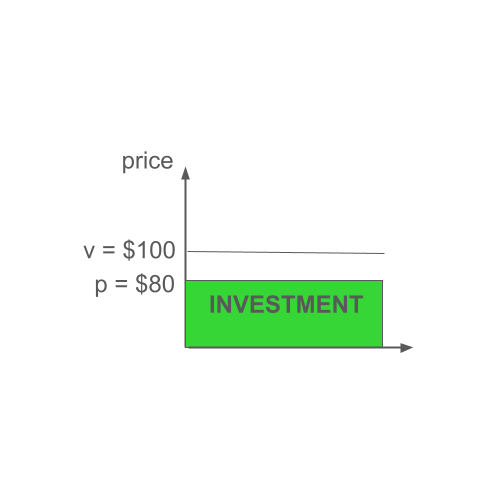

Of course, the real world is much more messy. Valuation is subjective, so even if one has access to all the available information, one can never have perfect foresight, so there must be a buffer. For example, you can estimate the value of something at $100, but there is uncertainty about the future, so for a purchase to truly be considered investing, you need to be able to buy it at a discount. How much of a buffer is needed is a subjective choice, but let’s use 20% as the margin of safety. The trade now looks like this:

Remember Ben Graham’s definition of investing:

An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.

If we take Graham’s definition literally, the trading scenarios would look like this:

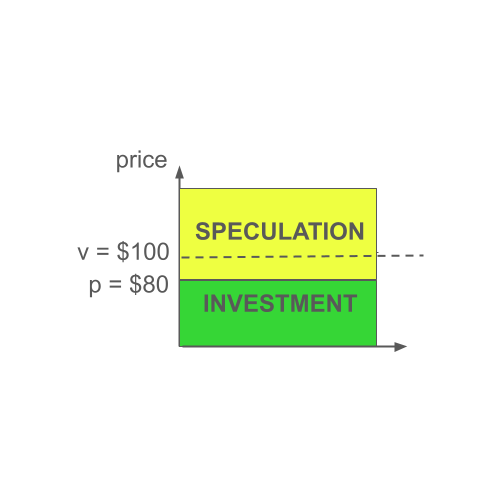

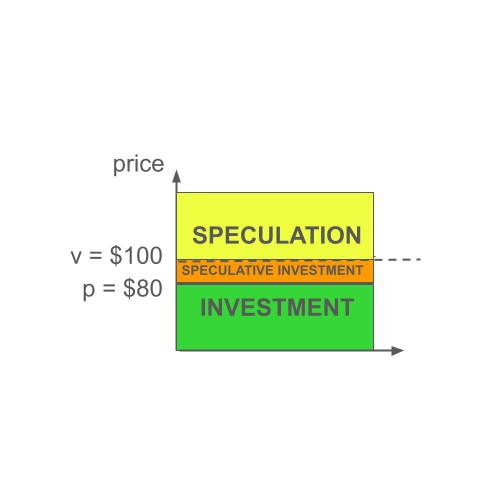

That’s not wrong, but we believe there is an even better way to illustrate this. Many things in life exist on a spectrum, with some sort of transition between the two. The day does not turn into night in one second; similarly, investing doesn’t turn into speculation like that. Rather, investing turns into speculative investing first and at some point becomes pure speculation. Now, the trading scenarios look like this:

Let’s get back to the numbers again through the lens of an investor:

Let’s assume you went through the valuation exercise (looking at the cash flows) and determined that the fair value of an asset is $100. In practice, your estimate would be not a point estimate but a range, maybe $80-$120. But for the purposes of this example, as well as decision making, let’s take the midpoint, and pin the value estimate at $100.

You determine that a 20% buffer is good enough considering your risk tolerance. You determine that the investment price of this asset is $80, meaning that at any price below that (barring the arrival of any new information), the purchase constitutes an investment.

What if the price is $90? It is still below your value estimate, but it is not low enough to be considered as an investment. That does not necessarily mean that you won’t transact at this price, you very well may. However, you are well aware that you now veered into the speculative investing territory where the price is still somewhat cheap, but not cheap enough to be considered a true investment.

Anything above $100 would be considered pure speculation. Again, that does not mean that you won’t trade when the price is above $100. You are just well aware that you are speculating and you are making a conscious choice. Just like a driver who simply wants to go fast but understands the consequences. When the speed limit is 55 miles per hour and they choose to go 75 miles per hour, they wouldn’t be under the illusion that they are obeying the laws. They simply make a conscious choice risking being pulled over and getting a citation.

This really is it. That’s the concept of investing. This is what Buffett said:

What you really want a course on investing to be is how to value a business. That’s what the game is about…If you look at what’s being taught, I think you see very little of how to value a business.

The challenge with investing is not conceptual; rather, it’s the valuation analysis. The world changes fast, perhaps even faster than before, and nobody knows what the future will bring. So when we casually say, “Let’s assume you went through the valuation exercise (looking at the cash flows) and determined that the fair value of an asset is $100,” that step is not a trivial one. It takes some mathematical savvy, but more importantly a good deal of foresight. Steve Jobs once said, “A lot of times, people don't know what they want until you show it to them.” If consumers don’t know what they want, how will you know how much somebody else’s product will sell for, and for how long? The buffer is a good idea for precisely that reason because it protects you, the investor, against the uncertainty.

Once you have your valuation down, there is no serious debate to be had as to whether a particular trade is investing or speculation. Sure, we can disagree how much margin of safety is enough and people may have different preferences, but for most people the choice set will look quite similar.

This framework has important implications for crypto. Let’s use Bitcoin as an example. Since there are no cash flows to Bitcoin, one cannot value it, and therefore one will never be able to establish a true valuation for it (or any other crypto that does not have cash flows for that matter). Further, since one cannot value it, one cannot invest in it.

So, when people say Bitcoin is speculative investing (and there are many of them), does that statement really make sense? Tune in for our next post.