From Bucket Shops to Prediction Markets

Democratization without prudence

Yesterday, we released a podcast walking you through the colorful history of bucket shops– the 19th and early-20th-century upstarts that became a formidable competitor to organized exchanges. The exchanges went on the offensive and litigation became their primary weapon. It wasn’t cheap, and it wasn’t quick (PDF):

[P]rotracted litigation … had cost the [Board of Trade] about $120,000 and had spanned 25 years, 248 injunctions, 27 jurisdictions, 20 cities, and 11 states.

So, yes, it took a while. But then SCOTUS killed it.

Almost.

While the Supreme Court’s Board of Trade decision in 1905 (PDF) marked the beginning of the end for bucket shops, the shops themselves tried desperately to hang on. They were down, but not out.

Then came 1907.

The 1907 Panic

We’ll dive deeper into the 1907 Panic in our next LexBeyond podcast (Ep. 15), but here’s the short version. Banks and trusts were at the center of the crisis. J.P. Morgan famously locked the bankers in a room, pledged a significant amount of his own capital, and forced a coordinated rescue. It worked–and cemented his status as a national figure. This panic also set the stage for the creation of the Federal Reserve.

While it’s rightfully remembered as a banking panic, there’s evidence that excess speculation at bucket shops magnified the crisis. From Sapien’s Financial Weapons of Mass Destruction: From Bucket Shops to Credit Default Swaps (PDF):

While CDSs may only be about a decade old, they are linked to a fundamentally similar, equally risky arcane financial instrument, which helped bring down the market in the Panic of 1907, known as the bucket shop.

The more one studies the rhetoric at the turn of the 20th century, the more today’s playbook starts to appear recycled.

Parallel #1 - Democratization of Access

At first, the exchanges weren’t particularly worried about bucket shops:

At first, as the Board of Trade’s official historian Charles H. Taylor noted in 1917, “they were not viewed with particular alarm” but regarded as “a sort of democratized Board of Trade, where the common people could speculate.”

Let’s rewind that.

A sort of democratized Board of Trade…

On one side: The financial establishment–old money, organized, regulated (at least somewhat).

On the other: The newcomer– new money, shut out of traditional channels, promising opportunity for everyone.

Sound familiar?

It should. It’s also virtually the same message we heard in Armstrong’s Davos wrap-up:

Tokenization will democratize access to high quality investments, as there are about 4B adults who don’t have access to these markets today (the “unbrokered”).

The great equalizer. Access for the common people. Democratization.

The playbook doesn’t change. Only the characters do.

Parallel #2 - A Call for Inclusivity

Hochfelder again:

Bucket shop proprietors exploited the public’s uncertainty about the difference between speculation and gambling to present themselves as respectable brokers who catered to the small investor. In its 1899 Guide to Investors, Haight and Freese claimed that its facilities were “designed for the benefit of THE MILLION” who lacked the capital and experience to invest with high-priced brokers.

Bringing “the unbrokered” in. Inclusive and empowering on paper. But as Lex and Bianca aptly put it, this was predatory inclusion long before the term existed.

The disruptor’s perspective: The old guard just doesn’t get it. There are millions of people who want this:

Millions. And they want to break free.

Parallel #3 - A Desire For Freedom

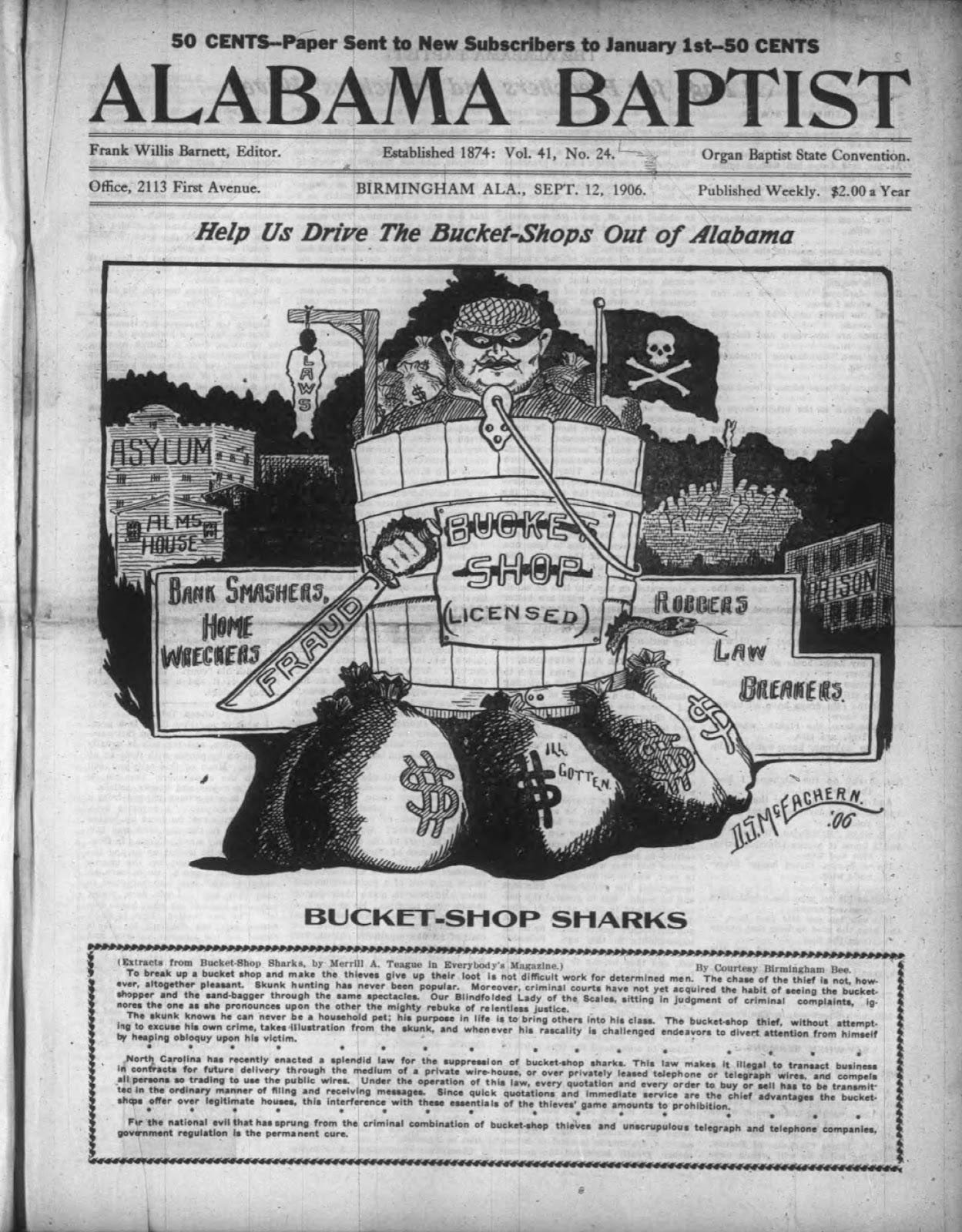

In 1906, Merrill A. Teague wrote a four-part exposé on bucket shops. The Alabama Baptist reprinted some of Teague’s excerpts (PDF):

Teague’s stance was clear, but he still gave the other side a voice and incorporated it into his reporting. Enter C. C. Christie, the so-called Bucket Shop King (PDF):

The Chicago exchange was “the biggest bucket shop on earth.” He accused the major exchanges of being grasping monopolists seeking “to crush the independents. It is a case of Greed versus Freedom.”

Freedom. Independence. The misunderstood “investor.”

It’s a familiar refrain. The bucket shops understood it in 1899. Organized exchanges didn’t. And if you ask the “Prince of Prediction,” 125 years later, they still don’t.

Guys like you who are a lot older… may not understand the demand of modern day investors.

Besides earning Coplan a middle finger, that quote revealed the bucket shop psychology. It doesn’t matter whether we are in the 1800s, 1900s or 2000s. The “modern investor” is always misunderstood, always oppressed, always in need of liberation.

And of course, Coinbase just wants freedom for America, too:

Final Thoughts

The echoes between bucket shops and today’s prediction and crypto markets aren’t academic curiosities, they’re warnings. Every generation rediscovers the same tension between access, prudence, innovation and exploitation, freedom and guardrails. Language evolves, technology improves, but the underlying pitch never changes:

This time is different and this time it’ll really be for everyone.

History is less forgiving. It reminds us that democratization without prudence will not expand your opportunities–it will expand your risk. When the cycle turns, it’s always the “common people” who pay the highest price.

As we march deeper into the world of prediction markets, tokenized assets and frictionless speculation, the question isn’t whether these tools will democratize finance. They might. The real question–the one that bucket shops answered the hard way–is whether democratization without prudence leads to empowerment or to the next preventable crisis.

History has cast its vote multiple times. The only question remaining is whether we act before the cycle repeats.