The Forbes Effect: Shoot First, Ask Questions Later

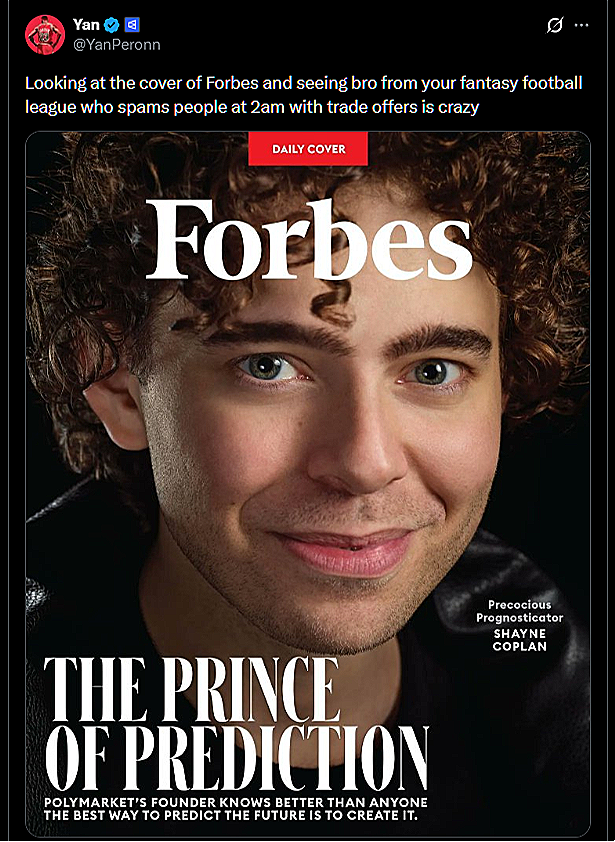

Will the “Prince of Prediction” become king? Or, will he be the latest fling?

Last week, we dissected the Bloomberg article titled Why It’s Harder to Tell Gambling From Investing Nowadays (paywall). If we sounded strongly opinionated, it’s because inaccurate and confusing investment commentary stings more when it comes from outlets you trust. Bloomberg is one of our favorite publications. Matt Levine, who writes Money Stuff there, is one of our favorite authors. So when Bloomberg misses the mark, or Matt Levine disagrees with Warren Buffett on what investing means, the disappointment cuts deeper.

But make no mistake: Bloomberg is no Forbes. When the confusion stems from centuries-old debates, nuance may be lost; that’s understandable. Forbes, however, seems less concerned with nuance and more with spotlighting whoever is “hot” in the business world at the moment. Snap a photo of the entrepreneur making waves–regardless of how those waves were made–and slap it on the cover. It’s the business journalism equivalent of the basketball cliché: Shoot first, ask questions later.

The list of Forbes 30 Under 30 selections that aged poorly is quite long. Entrepreneur Chris Bakke, who has multiple exits under his belt, (including one from Elon Musk), frequently highlights these missteps:

Forbes’s response to the debacle:

As a news organization, Forbes lists capture some of the most prominent people and companies that have profound impact at the time of publication. When fortunes change or new details are discovered, we are among the first to report on the news.

And again:

Forbes lists are a ‘snap shot’ of prominent people at that moment in time. The names mentioned below were on our radar (and many other media outlet’s radar) because they were already raising tens—or hundreds—of millions of dollars for top investors.

In other words: Forbes doesn’t care what’s under the hood. It’s a popularity contest, not a rigorous ranking of businesses built on substance. Once again: Shoot first, ask questions later.

Is that acceptable? We suppose it depends on what you want or expect from a top tier business magazine. Forbes claims its Under 30 lists are vetted by editors and “industry-leading judges.” But vetted under what standards? From where we sit, Forbes appears to have little to no filtration. Is the following acrostic too harsh?

Fraud

Or

Regulatory-

Based

Entrepreneurial

Success

To be clear, this critique isn’t aimed at the hardworking entrepreneurs who make this list. Many are principled builders who gave everything to their ventures. We recently corresponded with Chia Jeng Yang, who reached out to us after reading our Kalshi’s Gambit post; he’s smart, respectful, insightful and appeared on a regional 30 Under 30. This is a new relationship and our first impression is that people like him deserve more recognition. But when Forbes places genuine builders alongside multitudes of fraudsters and regulatory arbitrageurs, it dilutes not only its own brand but theirs as well.

This creates a classic adverse selection problem. Forbes supposedly has more information about the pool than individual candidates. Yet if candidates believe one bad apple will spoil the bunch, they may decline participation. If enough principled entrepreneurs sit out, what remains are those unconcerned with reputation–already not the best “apples.”

Being on the Forbes list should be an accomplishment. It should open doors, serving as a victory lap for sweat equity. But if for every two principled entrepreneurs there’s one bad actor (Bakke’s estimate), the reputational benefits must be weighed against the reputational costs:

Whether 35% is accurate or not, the blunders are undeniable. This brings us to Forbes’s latest cover–will this be yet another negative checkmark?

Shayne Coplan and the Regulatory Wave

Coplan was also on 60 Minutes:

Right out of the gate, Coplan described Polymarket as:

It’s a site where you can basically bet on current events.

Should we appreciate his honesty? Coplan isn’t even pretending that he is running a gambling outfit. By contrast, Kalshi’s CEO, Tarek Mansour, constantly oscillates between describing his platform as gambling and as financial innovation. Dustin Gouker has the receipts.

This reality that Coplan’s honesty reveals, on the other hand, is beyond debate. Just last week, we criticized Bloomberg for painting the entire prediction market industry with too broad a brush, calling it all “wagers.” As a matter of law, that’s simply not true. Yet here is the CEO of one of the largest platforms, reinforcing that very narrative himself.

This raises an even bigger question: If Coplan is just running a giant betting website, what exactly is he doing on the NYSE trading floor? It seems to always come down to the incentives, doesn’t it? Intercontinental Exchange, the company that owns the NYSE, invested up to two billion dollars in Polymarket, recently valuing it at roughly $8 billion, pre-money. Arguably, the valuation is even higher now. But, is it really worth $8 billion?

Valuations tend to hinge on belief. Do you expect SCOTUS to follow the law where it leads, prioritizing legal analysis over market enthusiasm–knowing that their decision will echo across presidencies for decades? We do. And when we tried to estimate the odds internally, we discovered a bit of a variance. But ultimately, two facts stand out:

America worked hard at keeping gambling out of the futures markets for over a century and that preference is codified in law; and

The majority of Polymarket’s event contracts are, by Coplan’s own admissions, bets.

Depending on your probability estimate, Polymarket’s valuation may be closer to zero than to $10+ billion. That’s how important definitional clarity is. As we detailed in our latest podcast, this isn’t even a billion-dollar issue, it’s a trillion-dollar one.

Are we surprised Coplan made the cover? Not really. To be clear, we’re not suggesting that he will end up in prison. Under the Commodity Exchange Act (“CEA”), offering a prediction market involving gaming isn’t criminal–it’s simply something the CFTC should take action on. They haven’t, and likely won’t. The proper grievance lies with the regulator itself, not Polymarket or Coplan.

Ironically, under a strict reading of the statute, someone like Jason Robins may be more exposed.1 Offering sports event contracts on a designated contract market (DCM) is less problematic than offering substantially similar contracts off-exchange. Historical realities, like the fallout from the 2008 crisis, help explain why.

Legal voices have already warned that federal preemption could upend state-regulated sports gambling. Brogan Law suggested that as a possibility:

An equilibrium that relies solely on the lack of action by a federal agency implies no right or privilege, and so if these state regimes were ever challenged on this basis, I believe there would be a robust, sound argument that they are preempted.

The Nevada Resort Association echoed this sentiment when it followed the preemption argument to where it leads and concluded:

To the extent that the sports bets offered by Kalshi are considered to be swaps and so the CFTC has exclusive jurisdiction over such swaps, then this could even require other types of sports bets to be only offered on a CFTC exchange.

And in a striking moment before the 3rd Circuit, the state attorney representing the state of New Jersey presented the real “come-to-Jesus” moment:

…[S]waps have to be traded on CFTC-regulated exchanges, on a designated contract market. And in fact it’s a federal crime to trade them outside of those scenarios. And so what we have here, is a definition by Kalshi, that would essentially make all casinos and sportsbooks currently federal felons. (emphasis added)

The state attorney continued until one of the Judges interrupted:

It seems that the definition of swaps is actually quite broad. And I understand you point out some things that seem undesirable to your side but…

Incremental inaction by the CFTC has been pivotal for that undesirable outcome:

It allowed daily fantasy sports to survive, which was instrumental in getting Murphy to be heard by SCOTUS;

It enabled state-regulated sports betting, post-Murphy;

It opened the door for Kalshi and Polymarket;

And now, it may have paved the way for nationalized sports gambling–the biggest prize of all.

Catch one of these waves and you just might land on Forbes’s cover.

The Wire Act Reminder

A quarter century ago, Jay Cohen went to prison for offering “sports futures.” The basis? The Wire Act. The law hasn’t changed, but government posture has. DraftKings now edges closer to offering sports event contracts through a federally regulated exchange–yet Cohen, who arguably invented this product, was jailed and now cannot even be hired due to “lack of experience.” Someone please make that make sense.

Strip away the regulatory cover, and isn’t Coplan simply repeating history here by copying Cohen’s business model? In theory, nothing has changed, in practice, everything has.

Based on the current regulatory postures, if there were a prediction market on the “Prince of Predictions” facing prison time, we’d take the “no” at nearly any price.

Forbes Could Be a Lead Generator For Regulators, Instead it is Highlighting the CFTC’s Own Failures

Chris Bakke captured this irony well:

Once, the Forbes list might have helped regulators identify wrongdoing. Today, they may highlight which regulators aren’t enforcing the laws they should.

Four years ago, the CFTC scrutinized Coplan’s business, and now he is featured on the cover of Forbes. Why? Because, in our opinion, the CFTC failed on two of its key decisions:

It abandoned the economic purpose test after 25 years; and

It failed (PDF) to act on sports event contracts.

Will the Forbes’s curse strike again? SCOTUS may have the final say.