The Needless Confusion Between Gambling and Investing

Even Bloomberg gets it wrong, contributing to decades of misinformation

Last week, Bloomberg Markets ran a piece titled Why It’s Harder to Tell Gambling From Investing Nowadays (paywall). Frankly, it’s becoming more difficult to read these articles without frustration. We seem to be stuck in an endless loop: Uninformed media publishing misinformation, respected outlets regurgitating them, and the cycle repeats.

We need a reset.

A reset requires acknowledging that some of the concepts we’ve carried for decades–sometimes centuries–are unsolved confusions. It’s a false dichotomy, a trap we unpacked in our inaugural LexBeyond podcast last week. The investing vs. gambling dichotomy.

These are the kinds of topics we explore here, on our sister blog Full Court Press and on LexBeyond. We dive deep, assume nothing, stress test everything and share our discoveries with you.

With that background, let’s dissect the Bloomberg Markets piece. Why is it more difficult to separate gambling from investing nowadays? The answers are hiding in plain sight, within the article itself.

The Subtitle Problem

With a tap on your phone, bet on football, elections and the price a stock will hit just hours from now.

Why is nuance so difficult to grasp? If everything is called a bet, then nothing is a bet. That’s an extreme position.

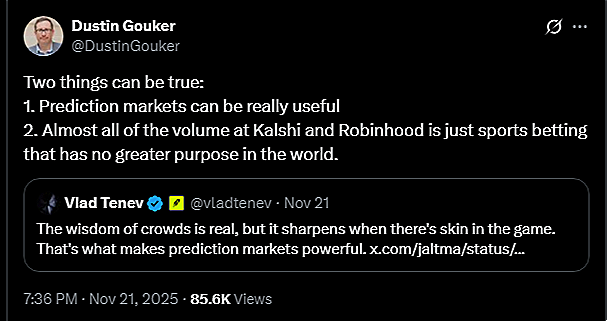

Dustin Gouker captures the right approach here:

Some prediction markets are worthy and they should be permitted. At the same time, some are unworthy and should be prohibited. The policy answer, then, is not all-or-nothing, it lies somewhere in between. The volume, however, is much closer to one extreme than the middle: As Gouker often notes, volume is heavily skewed toward sports event contracts. Those are the contracts that should never have existed in the first place.

The “everything is a bet” is an extreme position that only deepens confusion and hands ammunition to the other side. Its extreme nature not only makes the other extreme, “nothing is a bet,” equally plausible, but it also makes it more powerful because the latter receives significant support from two critical incentive dynamics:

Psychological: People feel better calling themselves investors rather than gamblers or speculators.

Financial: The desire to speculate on sports is innate, so most investors treat legal risks as a cost of doing business, funding platforms in hopes they grow “too big to fail.”

When the subtitle is misleading or flat out incorrect, can we really expect the rest of the article to deliver disciplined reasoning? You’ve likely seen this style of clickbait across the board–finance is no exception.

Options As Investments? Where Did That Idea Come From?

Bloomberg highlights Saha:

...a 25-year-old law student, tapped a phone app and bought $128 worth of bullish options, the right to purchase shares of uranium producer Cameco Corp. for $80 within the week. If they surged above that level, he could make many times his initial investment. If they didn’t, the options would expire, worthless—a total loss.

Stocks can be investments. Options, the types Saha trades, are contracts on stocks. Perhaps that proximity led to the mistaken idea that options themselves are investments. But options were designed to be portfolio insurance, not additional investments as part of your basket.

Unlike your health insurance, however, options can be purchased without owning the underlying asset. That wasn’t always the case with insurance either; 18th century England allowed “life insurance” on politicians and other celebrities, paying out on their deaths. The insurable interest rule emerged from that debacle, requiring a genuine stake in the outcome.

Prediction markets love to brand themselves as “innovations.” In reality, they’re older than America–even with contracts outside of sports.

Back to options: Many use them as pure speculation plays, which is just fine, they just should not be sold and marketed as investments because they surely are not that.

The Fading Line Between Investing and Gambling–Who’s Responsible?

Bloomberg claims Saha’s extracurriculars illustrate the fading line. Yet the record shows his goal is simple:

The goal is just to make my money grow… If it happens to grow large enough that I can pay my tuition with it, that’d be great.

He’s certainly permitted to do that, isn’t he? Using the options (pun intended) available to him? If one app (looking at you @Robinhood) consolidates every money-making possibility, that’s a policy problem, a legal problem, and a financial literacy problem. It’s not Saha’s problem.

Making money is not the same as investing.

PolyMarket: A Betting Platform or More?

In October, New York Stock Exchange owner Intercontinental Exchange Inc. said it would invest as much as $2 billion in the cryptocurrency-based betting platform Polymarket.

Yes, Polymarket and Kalshi have hosted questionable contracts (i.e. people throwing sex toys during sporting events), and many others. Still, there are a few legitimate contracts out there.

Once the term “bet” is applied universally, platforms and participants can weaponize the ambiguity. A mostly-gambling platform can rebrand itself as “investing,” while investors can dismiss legitimate hedging as “gambling.” The result is a proliferation of gambling, but the result would be different if the statute was interpreted properly.

In other words, if everything is a bet, nothing is a bet.

Hey, Bloomberg! Not All Event Contracts Are Wagers

Bloomberg lumps CPI, earnings calls, and NFL games together as “wagers.”

CPI contracts can hedge debt or rental agreements indexed to inflation.

Earnings call contracts may serve as hedges if structured properly. But “mention markets” based on CEO chatter? Those should never exist.

NFL games–we’ll let you decide. ErisX tried to argue economic purpose years ago. We pushed back in a letter to the CFTC (PDF), as did many others. Those contracts went nowhere. The CFTC’s position is very different now, and Commissioner-elect Selig signaled that he will let the courts decide.

Generalizations are dangerous. America worked hard to draw boundaries that Bloomberg casually erases. The reset won’t come from banning all event contracts. It will come from enforcing boundaries with discipline.

A Few Good Questions, A Few Bad Errors

Bloomberg finally asks:

If every interface becomes a casino, where does responsibility lie? With the trader? The tech? The system itself?

Great questions to be asking. Responsibility rests with the regulators, though courts will ultimately decide, especially on sports contracts. But courts need sound definitions in order to form the proper framework, which includes a responsible finance ecosystem and a cooperating media.

Bloomberg also misstates facts. The CFTC did try to shut down election contracts. It did not attempt to shut down sports contracts, it chose silence instead.12 These are easy fact checks and shouldn’t be slipping past editors, especially with the presence of AI.

Kalshi argues its contracts help companies hedge against real-world risks, such as a corporation worried about the victory of a politician promising a tax increase or an ice cream shop concerned about cold weather hurting sales.

Where are the editors, honestly? Kalshi may have anticipated making that argument, but in the end it didn’t need to–because the CFTC had already disclaimed authority. To the extent Kalshi continues to float this line now and then, it’s more about shaping public perception than about the actual legal victory. Economic purpose is certainly not why they won the legal fight.

Confusion is Not Complete Without Some Crypto

Bloomberg notes:

Under US law, betting on a baseball game is illegal in some states. But wagering on a Dogecoin swing, on the basis of nothing more than vibes, is fair play.

Well, our position remains that sports gambling is prohibited everywhere under federal law, though the Murphy decision, the subsequent proliferation of sports betting under the state regime and the CFTC’s inaction substantially complicated that picture. Our latest amicus brief (PDF) elaborates. But let’s focus on Dogecoin.

Wagering on a Dogecoin swing? That’s almost always gambling when structured as an event contract, because it’s hard to imagine any bona fide commercial risks tied to a memecoin (no economic purpose), which happened to begin as a joke in the first place. Buying Dogecoin outright, however, is not gambling–it’s speculation–and that distinction is paramount.

Final Thoughts

We urgently need a reset around these four words:

Investing, speculation, gambling, gaming.

This isn’t philosophical hair-splitting. These four words literally define the entire ballgame. Misusing them blurs boundaries, distorts policy and confuses the public. We are dedicating ourselves to clarifying these distinctions because we understand the consequences. We hope you will accompany us on that journey.

In January 2025, the CFTC announced that it notified Nadex (d/b/a crypto.com) it will initiate a review of the two sports event contracts Nadex self-certified in late 2024. It did not disclose the findings of that review.

Nadex was previously HedgeStreet, the name change happened in 2009. In late 2011, Nadex self-certified its political event contracts, which the CFTC denied in 2012 upon review. Crypto.com agreed to acquire Nadex in late 2021.