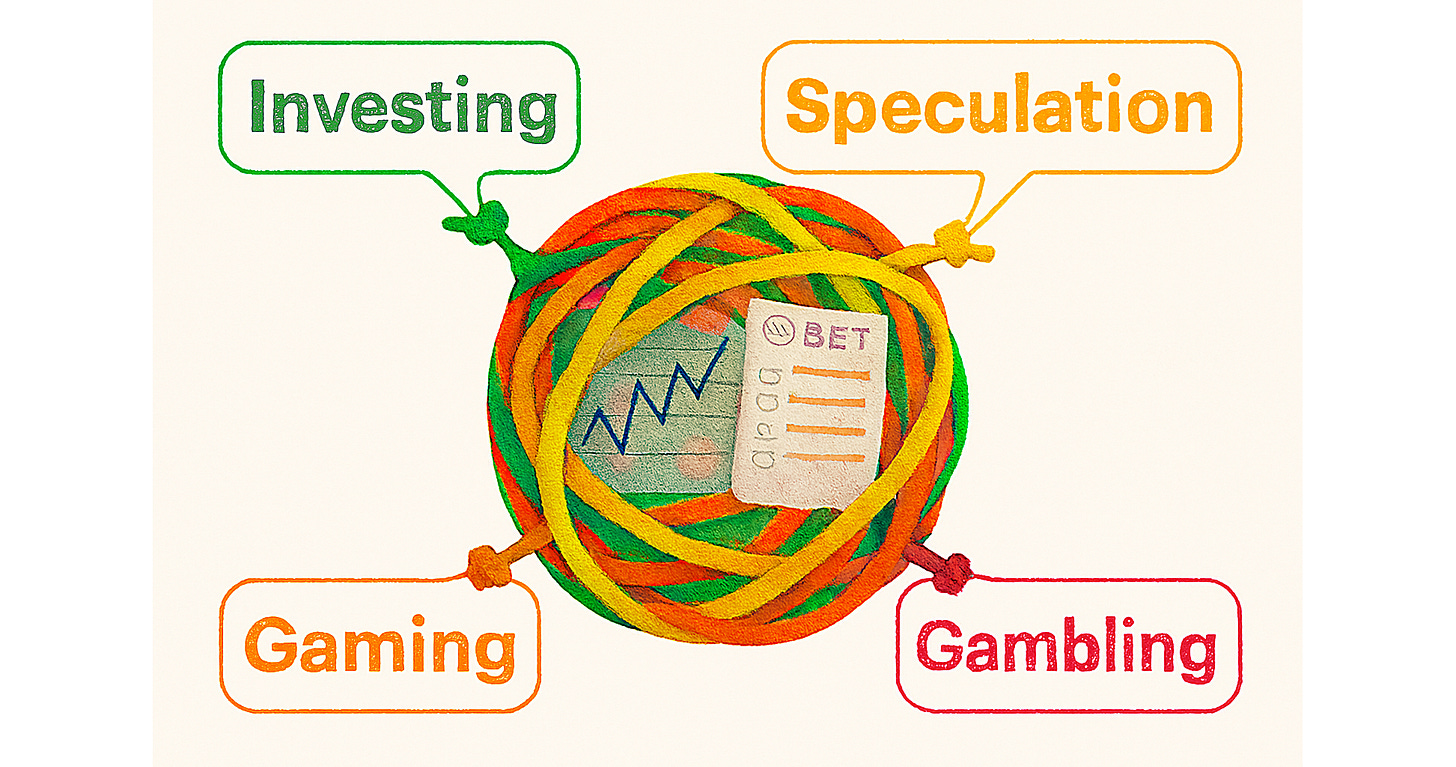

Why Investing, Speculating, Gambling and Gaming Are Colliding Into One Giant Headache

Markets are entangled in a hot mess

There’s a real possibility that Kalshi and Polymarket won’t be remembered for their sports event contracts. We believe those will eventually be outlawed by the courts. Election contracts might leave their mark (assuming that those don’t get reversed on economic purpose grounds), but even that may not be their legacy.

Instead, their historical significance may lie in forcing America to rethink what these four words actually mean:

Investing

Speculation

Gambling

Gaming

Last week, the New York Times ran an opinion piece titled Gambling. Investing. Gaming. There’s No Difference Anymore. We believe they missed the fourth one: Speculation should have been in the mix. Still, any title that includes three of these four words is screaming: Read me.

It’s no surprise this conversation is entering mainstream media. Dustin Gouker nailed the trend:

Prediction markets are raising lots of money and getting bigger, which means major media outlets are starting to cover the industry more closely.

Yes, and coverage is only going to accelerate. These four words are so entangled, untangling them will take time.

The NYT Piece: Timely, But Tangled

The topic is timely, and the attention is certainly deserved. The article offers some solid insights–and some that leave the readers wanting more. Let’s start with the good:

On the app of the investment brokerage Robinhood, users can now buy stocks on one tab, “bet” on Oscars outcomes on another, and trade crypto on a third.

Prediction markets and crypto. That’s our world. We’ve long discussed the perceived equivalence between stocks and crypto, and how that perception leads to subpar societal outcomes. Chief among them: Millions of people speculating without realizing they’re speculating.

The problem isn’t speculation, per se. When it comes to ownership of perpetual assets (as opposed to prediction markets), people should be free to speculate–whether it’s on stock or crypto. The problem exists in them believing that they are investing, when they aren’t–they’re speculating and that is a very slippery slope. That confusion stems from the incentive structure that is blurring the lines between the two.

Generally speaking, when things become entangled, they tend to entangle even more, before they get untangled. Prediction markets are now sliding into investing’s DMs. Why? Because the line between financial instruments and gambling is blurring. By definition, financial instruments serve the public interest, gambling doesn’t. Said differently, prediction markets are one corner of the financial world where people are not free to speculate. Excessive speculation in prediction markets means the contract is gambling, and shouldn’t be listed in the first place.

So how do we get out of this mess? We start untangling–one step, one line, one news article at a time.

Let’s start that process now, by dissecting three lines from the NYT piece that misled more than it clarified:

1) States Have Jurisdiction Over All Forms of Gambling - A Misinterpretation

In 2018, the Supreme Court removed a major roadblock by allowing states to legalize sports gambling.

Not incorrect. But vague language like “a major roadblock” often morphs into “the only roadblock.” Consider this line from a recent InGame article:

And when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act in 2018, betting became a states’ rights issue.

Or, last year’s headline from The Atlantic:

Legalizing Sports Gambling Was a Huge Mistake

And again from The Atlantic, just last week:

Since the U.S. Supreme Court opened the door to legalized gambling in 2018…

The Supreme Court’s 2018 decision is widely perceived—by media, the public, and even some legal circles—as having opened the door to legalized gambling. Judge Abelson (Maryland), in Kalshi v. Martin, echoed this sentiment when he wrote (PDF opinion):

It was not until 2018, when the Supreme Court issued its ruling in Murphy overruling PASPA, that states were permitted to legalize sports wagering within their boundaries.

We disagree with Judge Abelson on several points, including this one. The NYT actually has the more accurate description: PASPA was a roadblock, not the roadblock. Dodd-Frank still looms.

As soon as states began “legalizing” sports gambling, the CFTC could have acted. In fact, it could have acted earlier–on daily fantasy sports. DFS is not a game. In essence, each DFS entry is a contract on multiple future contingent events, which makes them either event contracts and/or swaps–squarely within the CFTC’s jurisdiction.

It’ll be fun to watch when people catch up to that argument.

2) Gambling In the Stock Market - A Misnomer

Many Americans, primarily young men, also began gambling on the stock market, their wagers enabled by platforms offering unlimited day trades.

Let us be very clear: You can’t gamble in the stock market!

This one’s tricky, and we certainly get why it may feel like “gambling.” Gambling carries a moral connotation, but it should be understood as a legal concept. Why? Because:

We need to determine jurisdiction (based on the laws);

Whoever has jurisdiction then needs to decide whether the activity should be regulated or prohibited; and

Whoever is deciding, needs a standard for that decision.

The confusion is as old as the country itself. In 1792, Alexander Hamilton wrote:

I observe that certain characters continue to sport with the Market & with the distresses of their fellow Citizens. ’Tis time there should be a line of separation between honest Men & knaves; between respectable stockholders and dealers in the funds, and mere unprincipled Gamblers. Public infamy must restrain what the laws cannot.

Then there’s the influential finance article Who Gambles in the Stock Market?—cited over a thousand times (Wiley), and possibly over two thousand times (Google Scholar).

Our answer: No one. You can invest. You can speculate. If you are somewhere in between, it’s speculative investing. But no one actually gambles in the stock market, no matter how much it might feel that way at times.

Yet the confusion persists–even in legal academia. From a forthcoming Boston College Law Review article titled “Betting on Everything”:

Although the U.S. legal regime doesn’t use this distinction to separate investing from gambling, an echo of it can be found in higher taxes on short-term capital gains. In some ways, this can be thought of as a penalty on those who gamble in the stock market.

Nope. Investing and gambling aren’t neighbors. Not in the stock market. Not in futures markets. That’s why we decided to dedicate our first LexBeyond podcast episode to this very topic–launching on November 13, 2025.

3) All Prediction Markets Are Gambling - A Misalignment

Next came prediction markets, which allow users to bet on anything — from Taylor Swift album sales to the weather — while avoiding the regulations that inhibit licensed gambling companies.

Glancing at our work you might determine us to be anti-crypto or anti-prediction markets. But, if you read us carefully, you’ll see that we are neither.

We’ve never called for a crypto ban. We’re not even convinced that crypto markets are more fraudulent than the banking system or other markets. What we do argue is that crypto should not be allowed to be promoted, marketed or sold as investing. There is a better way.

The same goes for prediction markets. Not all are legitimate financial products. But not all are gambling either. In this case, extreme positions like these do more harm than good; neither is consistent with Congress’s mandate.

Congress wanted essential futures contracts to move forward and the frivolous ones to be left behind. The economic purpose test was the legal tool to separate the two. For nearly 25 years after that test was repealed, the CFTC remained aligned with Congress. Now? Substantial misalignment is rampant and the CFTC no longer believes in economic purpose.

NYT’s weather example is misplaced. Bloomberg published an article nearly 15 years ago featuring a company selling de-icing compounds–highlighting real demand for hedging extreme weather risks. That demand has been soaring thanks to climate volatility. We can debate how much hedging happens in weather markets today, but calling it a bet without even considering its utility (or the lack of understanding how to determine its utility), is not a serious inquiry.

Taylor Swift album sales? Another weak example. If the the NYT authors wanted to highlight actual bets from prediction markets, they wouldn’t have needed to look very far:

The Astronomer CEO contract; and

And many, many more. Simply spend a little more time looking.

It’s tough to take the authors seriously when they don’t even attempt to distinguish socially useful prediction markets from entertainment-only ones. That’s a shame because they’re tackling what may be the most important societal and legal issue of the 21st century.

This topic deserves better. Otherwise, untangling our way out of this hot mess will be a long, uphill battle.