Finance Doesn’t Have a Monopoly on Persistent Myths

They happen in physics, too

We believe we know what could be bothering some of you about our “value investing” discovery. On one hand, you haven’t found a hole in our reasoning. It all makes sense to you. On the other hand, it sounds too “crazy.” You just can’t fathom how our discovery may have been overlooked by practically the entire finance community for decades. How is this possible? Is nobody paying attention?

As unbelievable as it sounds, myths can persist for a very long time. There is no natural mechanism for a myth to be busted. In fact, one can argue that the longer a myth persists, the higher the chance it will continue to live on, not unlike a 90-year-old having a much higher chance of living to 100 (in the UK, almost 7% of 90-year-old women became a centenarian, and men were close to 4%) than a newborn baby (less than 1%).

Why? Because once a person, or a myth, reaches a certain threshold, they have already overcome many risks, and it is more difficult to knock them down. A newborn baby, or an emerging myth, on the other hand, is just getting started and there are so many things that can go wrong!

Once a myth crosses a certain threshold and begins to become an accepted truth, it just doesn’t occur to most people to question it. It has not been questioned in the recent past, so why bother? There could be a number of different reasons why a myth might persist, including the various incentive structures in place. The more time that has passed, the more likely that an entire ecosystem has been built around it. People make money off of the myth, academia has entrenched positions, etc., so why would anyone stir the hornet's nest?

Even our About page mentions this phenomenon: We said:

We really do believe that Oscar Wilde was onto something when he said:

“Popularity is the crown of laurel which the world puts on bad art. Whatever is popular is wrong.”

A cynic can say Oscar Wilde simply didn’t like popular things. We believe that he was making a very important observation about persistent myths. He understood that time, counterintuitively, may become a myth’s best friend.

Analyzed through that lens, finance cannot be expected to be the only discipline where myths persist. The fundamental forces that allow a myth to live on are the same. Wouldn’t we see them in other fields?

Indeed, we do. Let us share with you an observation in physics that has recently begun making the rounds…

This was the headline in a Scientific American article published on September 5, 2023:

Mistranslation of Newton’s First Law Discovered after Nearly 300 Years:

Similarly, a ScienceAlert piece on September 14, 2023 used this headline:

We've Been Misreading a Major Law of Physics For The Past 300 Years

What happened here? We are not going to go into the details of physics here, but should you feel inclined, you can feast on the press coverage above, and/or read this nontechnical piece by Daniel Hoek, the myth-buster. He is an Assistant Professor in Philosophy at Virginia Tech (his CV). Here is the journal article, published in Philosophy of Science.

We have always maintained that discovering a myth is a positive step, but it should always be followed with the next question: Why? What circumstances were in place for the myth to be born, survive, and perhaps even thrive? Daniel Hoek, as any good detective would, asks the question and discovers the answer:

How did so many experts and smart people miss this? That question bugged me too, until I did some digging a few years ago. It turns out that for most of its history, almost every available translation of Newton’s Latin Principia was based on the original 1729 English translation by Andrew Motte. Motte’s edition was published two years after Isaac Newton’s death, and he almost certainly prepared it without Newton’s knowledge or permission. While it is mostly a very good translation, Motte skipped one persnickety little word in the First Law: the word quatenus, meaning “insofar”. As a result, here is the translation of the First Law that he (and the rest of us) ended up with: “Every body perseveres in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a right line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impress’d thereon.”

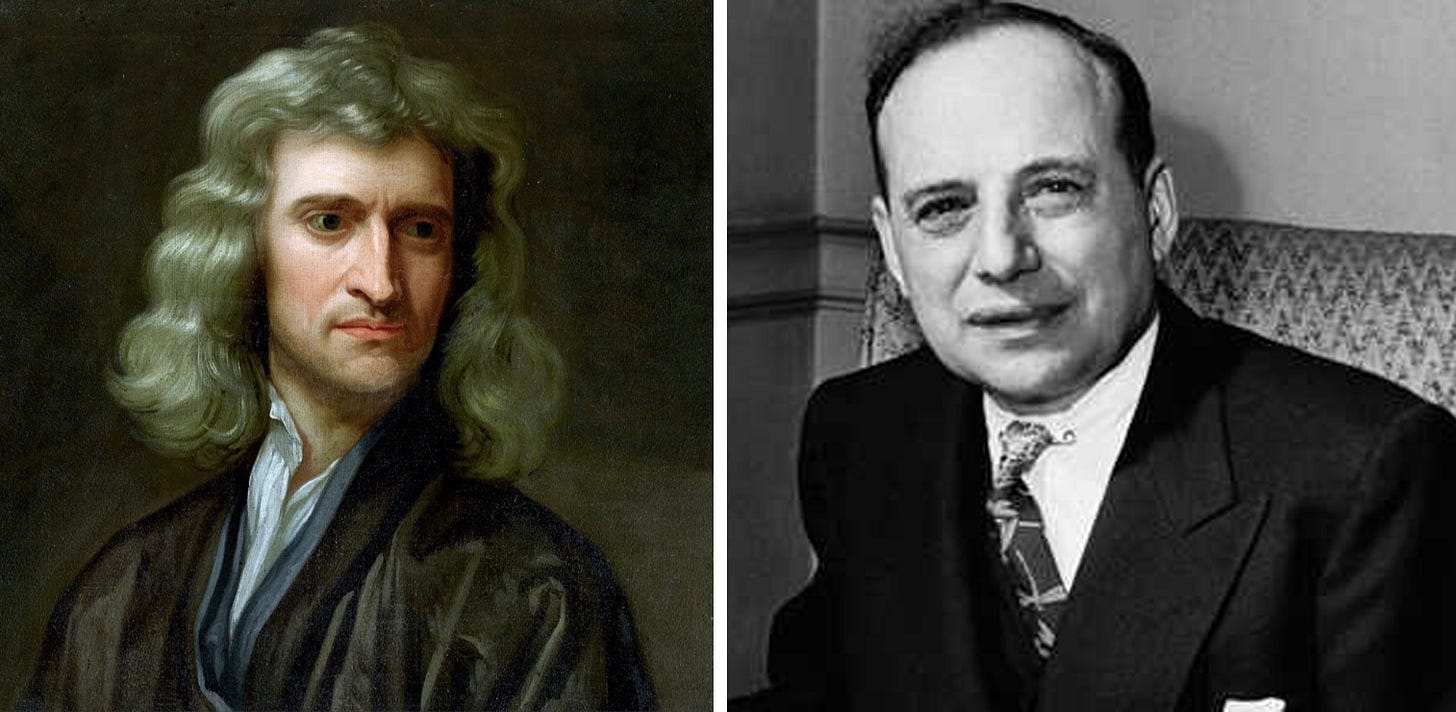

What we will do instead is compare the physics myth described above and the finance myth of “value investing.” These are the two OGs, the men whose work was misunderstood:

Image Credits

Sir Isaac Newton: shared by @johnthorewing

Ben Graham: Image Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The similarities are striking:

Being Judged Unfairly. The man on the left is Sir Isaac Newton and the man on the right is Ben Graham. Both found themselves on the wrong side of history for something they have not said.

Persistence. The physics myth persisted for nearly 300 years. The “value investing” myth is a baby in comparison, only a few decades old, but it’s going pretty strong.

Convenience over Critical Thinking. Both myths involve men who are at the top of their field. Does it really make sense that a man of Newton’s caliber would have come up with, in Hoek’s words, “a law of nature that governs nothing?” Similarly, to this day, why has nobody questioned the fact that the man with the nickname “the Father of Value Investing” never uttered the phrase in his own book, The Intelligent Investor? Exploring the truth is hard. Jumping on the bandwagon is easier.

Timing. No matter how many headwinds a myth may encounter, it’s difficult for it to gain meaningful momentum when the OG is alive, who himself can bury the myth with just a few words. When the OG is gone, the responsibility to correct the myth falls on others. In both cases, the myths started just a few years after the OGs passed away. In Newton’s case, the translation was published two years after Newton’s death. In Ben Graham’s case, it likely started with the 1986 edition of The Intelligent Investor, the first edition published after Graham’s death. We speculated that a book publisher meeting may be the moment when it all started.

Language. In both cases, language is the main culprit. In Newton’s case, the issue was a translation mistake. With Ben Graham, it was a logical fallacy.

Despite all these similarities, one important difference remains. As important as Newton's misunderstanding was, Daniel Hoek doesn’t think the mistake necessarily changed the trajectory of physics. He said:

To be clear, I am not saying physics would have gone differently if Newton’s insofar had not been lost in translation. As I explain in my paper on this topic, Euler’s reformulation of Newton’s Second Law ended up making the First Law somewhat redundant. For that reason, the fact that people had the wrong idea about Newton’s First Law did not much hamper our understanding of Newtonian Mechanics as a whole.

This is not the case with the “value investing” myth, which has extremely broad implications from income inequality and financial well-being to law. We do believe finance would have gone differently if it wasn’t for the “value investing’ myth. It may appear that it is too little too late to discard the myth, but we still have a shot to get back on track; that’s why we are here.